Table of Contents

- How is intergranular corrosion defined?

- Mechanism of intergranular corrosion formation

- Causes of this type of damage

- Control: Metallurgical approach according to ASTM A262

- Materials susceptible to intergranular corrosion

- Why intergranular corrosion is dangerous

- Conclusions

- References

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Intergranular corrosion represents one of the most critical deterioration mechanisms in stainless steels used in the process industry. Unlike uniform corrosion, this type of attack occurs locally along the grain boundaries, compromising the structural integrity of the material without visible surface manifestations. Its presence is closely linked to metallurgical phenomena induced by inadequate heat treatments, welding, and incorrect material selection, making it a silent risk for refineries, chemical plants, and fluid transport systems.

How is intergranular corrosion defined?

Is defined as a preferential attack that develops along the grain boundaries of a metallic alloy, while the grain interior remains relatively intact. In stainless steels, this phenomenon is directly associated with the local loss of corrosion resistance due to chromium depletion in areas adjacent to these boundaries.

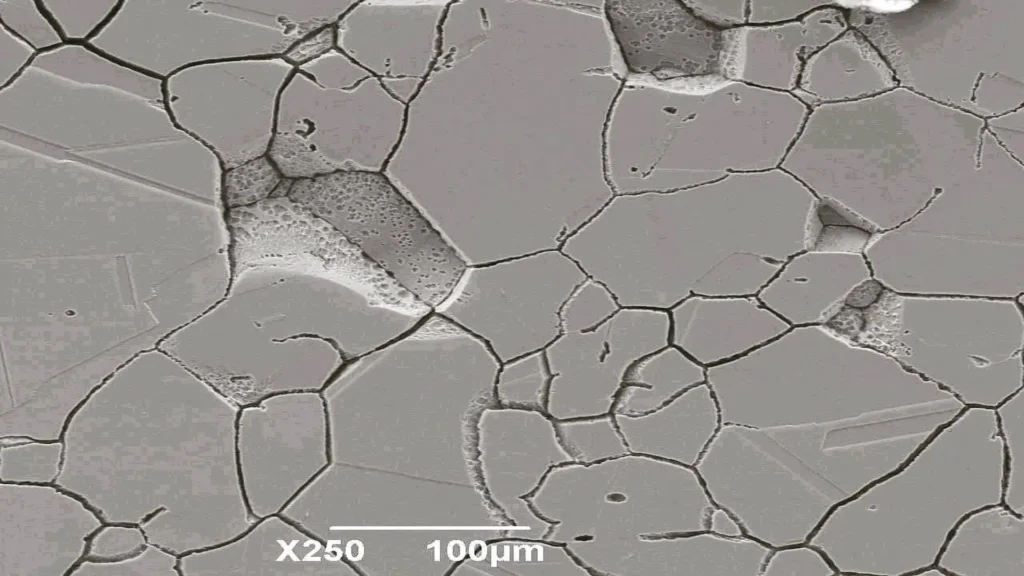

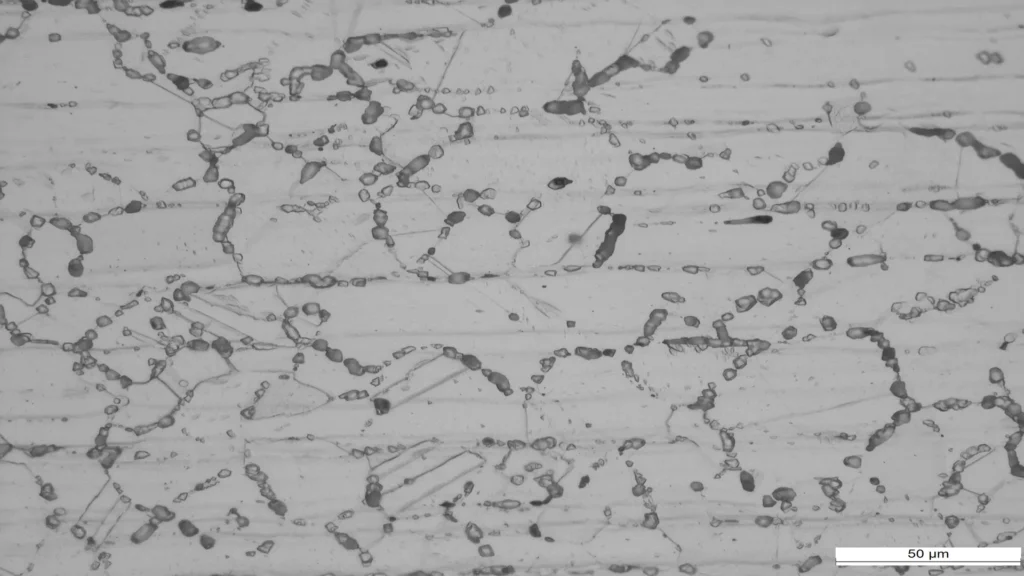

From a metallurgical standpoint, the problem is not chemical in origin but microstructural. The steel loses its passivation capability in specific regions, facilitating a selective attack that can lead to brittle fracture or total loss of mechanical strength. The following image shows a photomicrograph of a stainless steel with grain boundary corrosion.

Mechanism of intergranular corrosion formation

The classic mechanism of formation occurs when stainless steel remains within an approximate temperature range of 450 °C to 850 °C, known as the sensitization range. Within this interval, carbon combines with chromium to form chromium carbides (Cr₂₃C₆) that precipitate at grain boundaries.

This process is particularly common in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) during welding operations. Carbide precipitation reduces the available chromium content in areas near the grain boundary, bringing it below the threshold required to maintain the protective passive layer. As a result, these regions become highly susceptible to localized corrosion when exposed to aggressive environments.

Causes of this type of damage

Intergranular corrosion primarily originates from metallurgical conditions induced during fabrication, welding, or equipment operation. One of the most critical factors is welding without adequate thermal control, which exposes the material to the sensitization temperature range and promotes the precipitation of chromium carbides at the grain boundaries. This is compounded by the use of non-stabilized stainless steels in critical services, where the chemical composition of the material does not provide sufficient protection against carbon segregation.

The absence of post-weld heat treatments exacerbates this scenario by preventing the redissolution of formed carbides. Furthermore, prolonged exposure to intermediate temperatures during operation can induce sensitization even in equipment originally manufactured under controlled conditions.

Control: Metallurgical approach according to ASTM A262

Effective control of intergranular corrosion requires an objective verification of the metallurgical condition of the material before commissioning. In this context, ASTM A262 constitutes the fundamental technical reference for detecting susceptibility to this type of attack.

ASTM A262 establishes a set of standardized testing practices designed to identify whether a stainless steel has been sensitized, that is, whether it exhibits chromium depletion at grain boundaries due to carbide precipitation. The standard does not evaluate corrosion in service but rather the metallurgical predisposition to damage, making it an eminently preventive tool.

Testing practices and Application

The standard includes different methods, the selection of which should be based on the steel grade and its thermal history:

- Practices A and B: Acid immersion chemical tests used as preliminary evaluation.

- Practice C (Huey Test): Mainly applicable to stabilized stainless steels, allowing detection of residual sensitization.

- Practice E (Strauss Test): Designed for non-stabilized austenitic steels, especially in welded areas.

- Practice F: Electrochemical test for rapid detection in the laboratory.

Correct selection of the ASTM A262 method is essential to obtain representative and technically defensible results.

Control of the Heat-Affected Zone

The HAZ is the most critical region from the perspective of intergranular corrosion. Applying ASTM A262 tests to representative coupons from this zone allows the validation of welding procedures, confirmation of the need for post-weld heat treatments, and prevention of the commissioning of components with latent damage.

Integration into integrity programs

ASTM A262 should be integrated into quality assurance and integrity management programs, particularly in:

- Material qualification and acceptance.

- Validation of welds in critical equipment.

- Evaluation of components subject to prolonged shutdowns.

- Root cause analysis of premature failures.

This standard represents a preventive technical barrier against this type of corrosion.

Materials susceptible to intergranular corrosion

Susceptibility to intergranular corrosion largely depends on the material’s chemical composition and thermal history. Conventional austenitic stainless steels, such as AISI 304 and AISI 316, are particularly vulnerable when they have not been designed or processed to resist sensitization. In these materials, relatively high carbon content combined with exposure to the critical temperature range favors the precipitation of chromium carbides at grain boundaries, locally reducing passivation capability and enabling selective corrosive attack.

In addition to classic austenitic steels, certain duplex stainless steels and special alloys can also develop intergranular susceptibility if subjected to inadequate thermal cycles, such as slow cooling, high-heat welds, or poorly controlled heat treatments. In these cases, microstructural degradation is not always evident and may only manifest under aggressive service conditions.

Stabilized stainless steels, such as AISI 321 and AISI 347, incorporate alloying elements like titanium or niobium, which reduce carbon availability for chromium carbide formation. This characteristic provides greater resistance to intergranular corrosion, especially in welded applications. However, these materials are not completely immune. Poor metallurgical control, prolonged thermal exposures, or inadequate manufacturing procedures can partially negate stabilization benefits, making verification through standardized testing essential.

Why intergranular corrosion is dangerous

The danger of intergranular corrosion lies in its hidden and progressive nature. Unlike other corrosion mechanisms, this attack does not produce uniform thickness loss or visible surface signs detectable by conventional visual inspection. The degradation is concentrated at grain boundaries, weakening the internal structure while the surface appears acceptable.

Mechanically, intergranular corrosion significantly reduces ductility and fracture strength, increasing the likelihood of brittle failures. These failures can occur suddenly and without warning, particularly in equipment subjected to pressure, cyclic loads, or thermal variations.

In industrial environments, the integrity loss associated with intergranular corrosion directly compromises operational reliability. An unexpected failure can result in process leaks, release of hazardous substances, unplanned shutdowns, and high repair costs, as well as significant risks to personnel safety and the environment. For these reasons, this mechanism is considered one of the most critical from the perspective of integrity management and metallurgical control.

Conclusions

Intergranular corrosion is not an isolated problem but a direct result of metallurgical, thermal, and operational decisions. Effective control of this mechanism requires a deep understanding of the material’s microstructure, correct alloy selection, and rigorous application of standards such as ASTM A262. Integrating these criteria into asset integrity programs helps reduce risks, extend equipment life, and ensure operational safety.

References

- ASTM International. (2023). ASTM A262: Standard Practices for Detecting Susceptibility to Intergranular Attack in Austenitic Stainless Steels.

- Fontana, M. G. (2005). Corrosion Engineering. McGraw-Hill.

- Sedriks, A. J. (1996). Corrosion of Stainless Steels. Wiley-Interscience.

- ASM International. (2019). ASM Handbook, Volume 13A: Corrosion: Fundamentals, Testing, and Protection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Does intergranular corrosion only occur in stainless steels?

Primarily, although other materials with grain boundary segregation can also be affected.

Is ASTM A262 a destructive test?

Yes, it is applied on representative specimens to evaluate metallurgical susceptibility.

Is a stabilized stainless steel immune?

Not completely, but it significantly reduces risk if processed correctly.

Can it be detected with visual inspection?

No. Metallurgical testing or standardized tests are required for reliable detection.