Offshore operations represent one of the greatest challenges of contemporary engineering. Offshore platforms are strategic nodes for exploration, production and export of hydrocarbons. These structures depend not only on hydrostatic calculations, structural designs and advanced control systems, but also on the most critical resource: the human talent that operates, maintains and supervises them in extreme environments.

Engineering and people: an interdependent ecosystem

An offshore platform is a technical ecosystem where floating structures, drilling, storage and transportation systems converge. However, its operation is only possible thanks to highly specialized human teams: dynamic positioning operators, structural integrity engineers, welding inspectors, drillers, safety supervisors and logistical support crews.

The constant interaction between technology and the human factor turns these units into floating cities, where organizational culture, training and personnel resilience ensure operational continuity in the face of highly complex risks.

Platform typology and human competencies

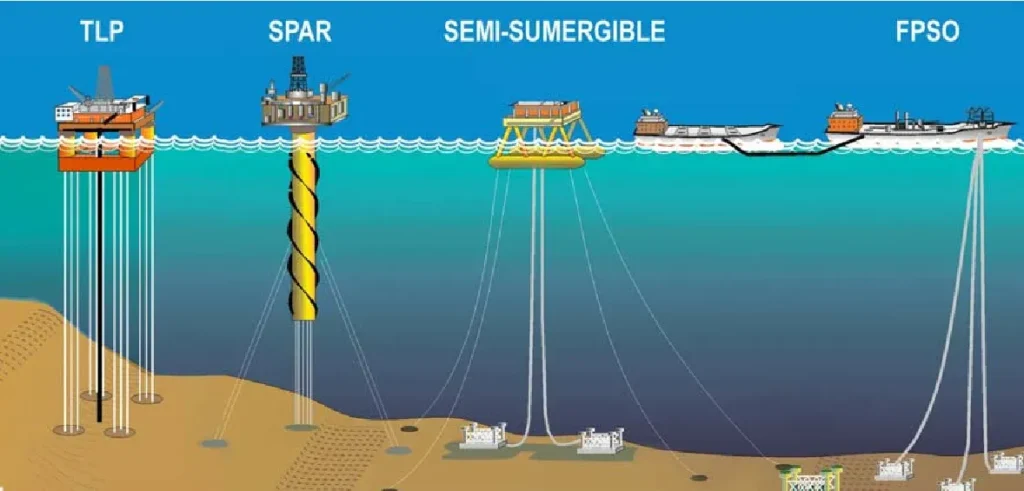

Each type of offshore platform places specific demands on both the engineering and the personnel who manage it:

- Semi-submersibles: Their stability depends on anchoring and ballast control systems. Field operators permanently monitor load distribution and correct deviations in real time.

- TLP (Tension Leg Platform): This type requires rigorous inspection. Structural integrity engineers and non-destructive monitoring technicians ensure their reliability.

- SPAR: Due to their large draft and dynamic response, they require specialists in hydrodynamics and operators of remote monitoring systems that evaluate vibrations and structural stresses.

- FPSO (Floating Production, Storage and Offloading): This is where the skills of seafaring, industrial processes and storage control come together. The human factor is considerable in the management of the turret mooring system and in the operation of integrated process plants.

Buoyancy and stability: more than calculations

The buoyancy of a platform is based on the Archimedes principle and optimized designs that balance center of gravity and metacenter. However, the theory translates into operational safety only through human intervention:

- Ballast operators: Guarantee dynamic balance in the face of load and swell changes.

- Corrosion and welding inspectors: Verify that the structure resists fatigue induced by load cycles.

- Maintenance crews: Execute emergency protocols in case of water ingress in watertight compartments.

Without these human functions, even the most advanced design would be vulnerable to extreme ocean conditions.

How is oil extracted offshore?

Offshore hydrocarbon extraction combines advanced technology with operational experience:

- Drilling: Engineers and drillers plan, operate drilling equipment and monitor well integrity.

- Production control: Technicians and control room operators monitor flow rates, pressure and temperature, ensuring production efficiency.

- Equipment maintenance: Specialized personnel perform inspections and preventive repairs to avoid failures in pumps, valves and oil and gas separation systems.

- Operational safety: Supervisors and operators implement emergency protocols for spills, fires or storms, ensuring the protection of the platform and crew.

Safety and sustainability: culture beyond standards

Offshore platforms operate under strict regulatory frameworks (API, ISO, DNV-GL), but their actual compliance is underpinned by the safety culture and operational discipline of the personnel.

- Continuous training: Simulation and emergency training programs ensure effective reactions to fires, leaks or storms.

- Fatigue management: Rotating shifts, rest protocols and psychological support are essential to maintain focus in high-pressure environments.

- Environmental commitment: Beyond marine monitoring systems, it is the awareness of operators that determines the effectiveness of contingency plans.

The operator as the axis of resilience

Offshore engineering faces high impact risks: storms, storm surges, accelerated corrosion, mechanical failures and operational accidents. Resilience is not only achieved with naval steel, simulation software or redundant systems, it is achieved because control room operators, deck engineers and field technicians act as the real protection system.

Conclusions

Offshore platforms are feats of modern engineering, but their safe and sustainable operation depends, ultimately, on the synergy between technology and human talent. Steel, hydrostatic calculations and automation are critical, but it is the skill, discipline and commitment of the human teams that turn these floating cities into resilient environments capable of supplying the world with energy from the depths of the ocean.

In offshore management, the real differentiator is not only in the structural design or control systems, but in the people who, day after day, make it possible for technological innovation to translate into safety, efficiency and sustainability.

This article was developed by specialist Yolanda Reyes and published as part of the sixth edition of Inspenet Brief September 2025, dedicated to technical content in the energy and industrial sector.