The degradation of metallic materials in industrial environments represents a challenge in structural integrity engineering, where the distinction between different corrosion mechanisms is fundamental to prevent structural failures that compromise the integrity and functionality of the components. As a specialist in the study of the chemical, electrochemical and mechanical behavior of materials, the persistent confusion between Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) and Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC), two processes that although they share certain similarities in their manifestation, such as crack formation, obey different underlying mechanisms and factors, is of concern.

This lack of clarity in their differentiation has led to the implementation of incorrect mitigation strategies, with potentially disastrous consequences for the safety of workers and the operational reliability of equipment. The distinction between the two processes is not simply an academic exercise; it is an imperative technical necessity to ensure proper selection of materials, heat treatments, coatings, and protection strategies that actually prevent premature component failure.

This article aims to rigorously clarify the differences between hydrogen embrittlement and stress corrosion cracking, emphasizing the importance of a correct characterization of their mechanisms and the accurate selection of control methods. Only through a thorough technical understanding is it possible to effectively mitigate these types of failure and preserve the reliability of industrial infrastructures.

What is Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE)?

Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) is a material deterioration process caused by the absorption of atomic hydrogen into the metallic structure. This phenomenon can considerably reduce the ductility of the metal, increasing the susceptibility to fracture under stress conditions.

Hydrogen is introduced into the material in environments containing acids such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) or hydrofluoric acid (HF), or through industrial processes such as welding or contact with chemicals. When hydrogen is absorbed by the metal, it dissociates into hydrogen atoms that can penetrate the crystalline structure of metals. This creates microcracks in the surface of the metal, leading to a loss of ductility and increased brittleness.

Types and effects on materials

Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) is a phenomenon that affects the strength and ductility of metallic materials, causing structural failures. Depending on the origin of the hydrogen, two main types can be distinguished: Internal Hydrogen Embrittlement (IHE) and Environmental or External Hydrogen Embrittlement (EHE). Each type and its implications on metallic materials are described below.

1. Internal Hydrogen Embrittlement (IHE)

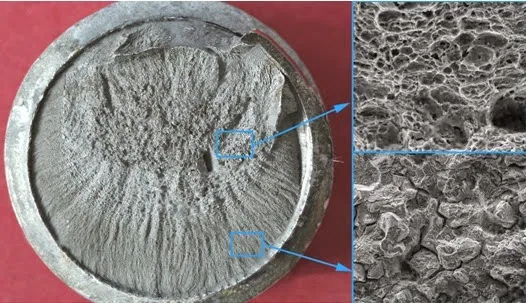

Internal Hydrogen Embrittlement (IHE) occurs when hydrogen is introduced into a material during manufacturing or processing, weakening its structure and reducing mechanical strength. This hydrogen trapped in the material’s microstructure can induce the formation of internal microcracks and compromise its structural integrity over time. Figure 1 shows an advanced three-dimensional image. Currently, such images are being developed to provide key information to predict metal fracture. In this study1, cracks in a hydrogen embrittled nickel alloy were identified as they propagated along grain boundaries.

Production, certain processes favor the absorption of hydrogen in metals. In these cases, atomic hydrogen is generated at the surface of the material and diffuses inward, mainly in high-strength steels. The processes with the greatest influence on hydrogen absorption include chemical pickling and electrolytic galvanizing. In the case of pickling, the acid solutions used generate hydrogen as a by-product, which diffuses into the metal material or component. During the electrogalvanizing process, hydrogen is also produced on the surface of the material, facilitating its diffusion into the metal structure and increasing the risk of embrittlement.

The phenomenon is particularly relevant in high-strength materials, such as high-alloy steel, nickel, and other metal alloys, which are more susceptible to hydrogen embrittlement. However, it can also affect materials such as copper, aluminum and stainless steel, although to a lesser extent.

2. Environmental or External Hydrogen Embrittlement (EHE)

Environmental or External Hydrogen Embrittlement (EHE) occurs when hydrogen is absorbed from the environment due to exposure to corrosive media, electrochemical processes or extreme environmental conditions. This type of embrittlement affects materials in service, compromising their durability and operational safety.

In EHE, hydrogen atoms diffuse from the outside into the crystalline structure of the metal, accumulating at grain boundaries, non-metallic inclusions or dislocations. Hydrogen is deposited on the metal surface, due to electrochemical reactions in the presence of moisture, especially in acidic media or with high concentration of chlorides, facilitating its production and subsequent permeability in the material. moisture plays a key role in the degradation of the material, since its presence is directly related to the severity of the corrosive process and, therefore, to the probability of embrittlement of the metallic component.

The hydrogen generated by these reactions infiltrates into the metal matrix and, in the presence of pre-existing microcracks, accumulates at their ends, favoring their propagation and triggering the embrittlement process. This localized weakening is further accentuated by the presence of corrosion pitting and oxide layers, which promote greater hydrogen absorption, especially in alternating wet and dry environmental conditions. The following image shows a brittle fracture-induced corrosion crack in a metallic surface. In the initial stage of propagation, the predominant mechanism is intergranular and brittle in nature, while in the final stage a ductile type fracture is observed (Figure 2)2.

What is Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)?

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) is very well defined by researchers3 who have reported the causes of this mechanism for the vast majority of alloys and low carbon metals, such as steels used for transporting hydrocarbons. Most authors agree that stress corrosion cracking is a type of localized corrosion, which occurs in the form of cracks on steel when it is susceptible to the presence of SCC and is simultaneously stressed and exposed to an aggressive environment.

Unlike Hydrogen Embrittlement, SCC does not require the presence of hydrogen, but is produced by the interaction of tensile stresses and a corrosive environment such as aqueous chloride solutions. This type of cracking is called hydrogen cracking, which induces the growth of cracks in the material. This type of cracking is mainly observed in metallic alloys, such as stainless steel, aluminum and titanium, although it can also affect other materials such as polymers and ceramics. There are two types of stress corrosion cracking: intergranular, when cracks develop along grain boundaries, and transgranular, where the crack forms across the grains of the material.

Comparison between Hydrogen Embrittlement vs. Stress Corrosion Cracking

Hydrogen Embrittlement is based on the absorption of hydrogen by the material, which reduces its ductility and deformation capacity. On the other hand, stress corrosion cracking is generated when the material experiences mechanical stresses and is exposed to a corrosive environment.

One of the most important points to differentiate Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) from Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) is to know and understand the mechanism by which this structural damage occurs4.

Mechanism of Hydrogen Fragilization (HE).

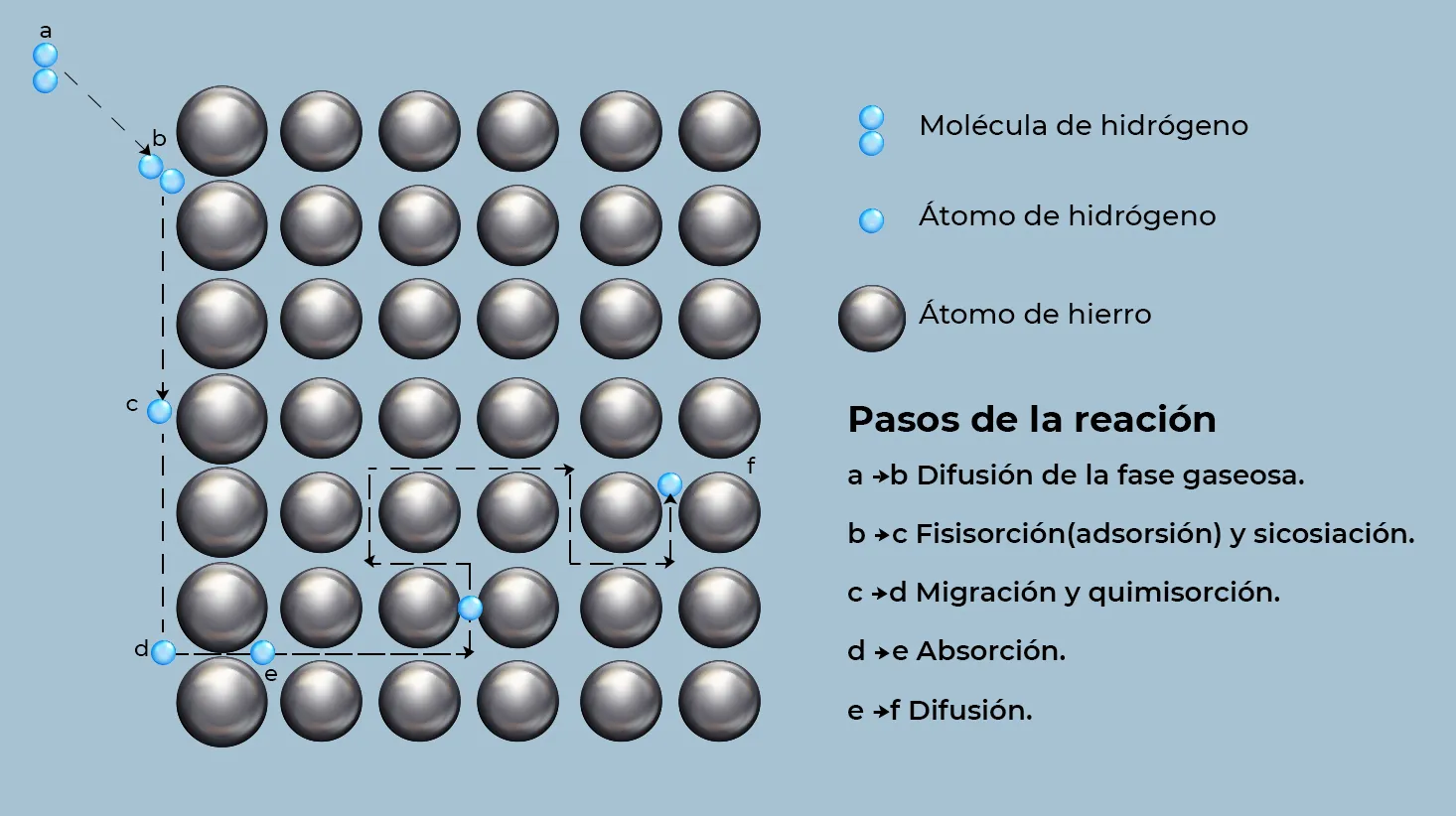

Hydrogen can originate mainly from two sources: an aqueous electrolyte (H₂O) or molecular hydrogen (H₂) in the gas phase. In both cases, hydrogen enters the metal in atomic or ionized form, acting as an interstitial solute. When coming from a gaseous atmosphere, the H₂ must first be adsorbed on the surface, then dissociate into individual atoms and finally diffuse through the crystalline structure of the metal. This process occurs because the hydrogen molecules are too large to move directly through the metal lattice, so their transport within the steel is accomplished through the migration of individual atoms.

Figure 3, illustrates the different reactions that occur during hydrogen diffusion in a metallic material, this illustration allows a better understanding of the processes involved in its transport within the crystal lattice5.

If the hydrogen source is an aqueous electrolyte, its transport to the metal lattice occurs by adsorption on the surface of the material, a phenomenon that can occur through two mechanisms: physisorption and chemisorption. Physisorption involves the adsorption of molecular hydrogen by Van der Waals forces, while chemisorption involves the formation of chemical bonds between the hydrogen and the metal. In turn, chemisorption can be either non-dissociative, in which the hydrogen remains in its molecular form, or dissociative, in which the hydrogen separates into individual atoms before being adsorbed by the metal. Only dissociative chemisorption allows effective incorporation of hydrogen into the metal structure6 .

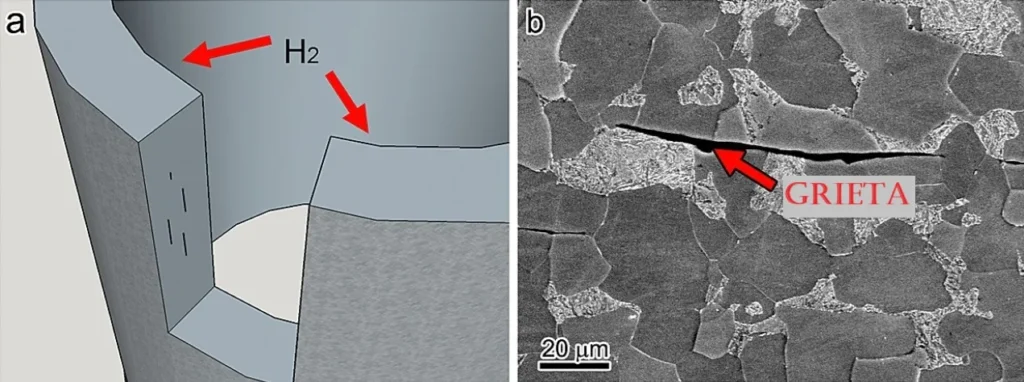

In the following image (Figure 4), micrographs obtained by SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) of a hydrogen embrittlement corrosion process are shown7.

Hydrogen Embrittlement results from the diffusion and accumulation of atomic hydrogen in the crystal lattice of the material, which induces a loss of ductility and an increased susceptibility to brittle fractures under load. In contrast, stress corrosion cracking occurs when a material under sustained mechanical stress interacts with a specific corrosive environment, facilitating the initiation and propagation of cracks in an intergranular or transgranular manner, depending on the metal-corrosive medium system involved.

Mechanism of Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

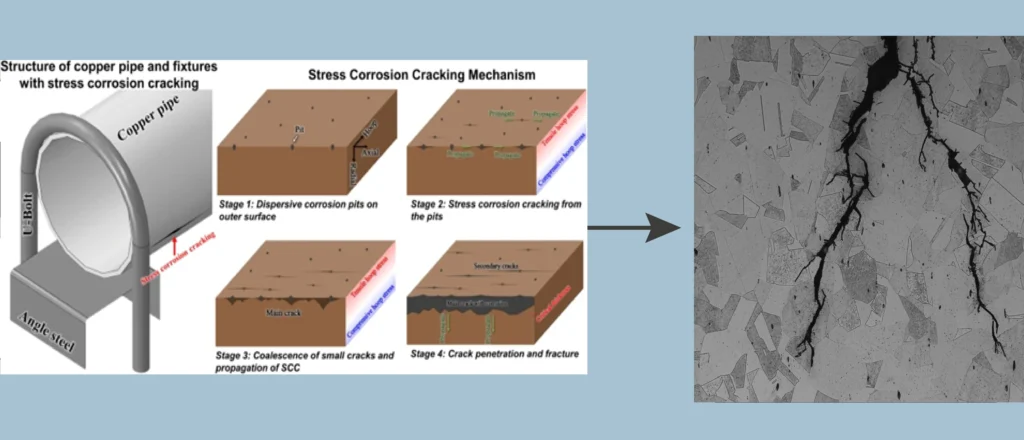

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) is a material failure process that occurs when mechanical stresses are combined with a corrosive environment, causing the formation and propagation of cracks. This type of damage, unlike hydrogen embrittlement, does not require the presence of hydrogen, but is caused by the interaction of tensile stresses and a corrosive environment such as aqueous chloride solutions, which induces crack growth in the material.

As the material is subjected to stress, the corrosive environment favors the formation of microcracks that grow and propagate under the influence of the applied stress. These cracks can be extremely small and not always visible to the naked eye, being difficult to detect without advanced inspection techniques. High-strength alloys are particularly susceptible to stress corrosion cracking, as the presence of internal and external stresses combined with exposure to a corrosive environment facilitates crack propagation8.

There are two types of stress corrosion cracking: intergranular, when cracks develop along grain boundaries, and transgranular, where the crack forms across the grains of the material.

Comparative summary of the most important differences between these two types of corrosion.

| Characteristic | Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) | Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Hydrogen absorption and reduced ductility. | Interaction between stress and a corrosive environment. |

| Affected Materials | Metals and alloys such as steel, iron, and nickel. | Primarily metallic alloys. |

| Environmental Conditions | Presence of acids such as H₂S and HF. | Small amounts of corrosive environments. |

| Temperature | Higher susceptibility at temperatures close to ambient. | Less dependent on temperature. |

| Detection | Difficult to detect without specialized inspection. | Microscopic cracks visible but difficult to identify. |

Hydrogen Embrittlement (HE) and Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) are two of the biggest challenges to the integrity of metallic materials in industrial environments. Although their mechanisms are different, both represent significant risks, especially in sectors such as oil, gas and power generation, where metals are exposed to extreme stress and corrosion conditions. Given the importance of these issues, the AMPP Annual Conference + Expo 2025, to be held in Nashville, USA, will be the key focus to discuss the latest research and mitigation strategies in this sector.

This event will bring together international experts in corrosion and structural integrity who will share knowledge on monitoring, inspection and prevention of failures associated with SCC and HE. The technical discussions will provide engineers, inspectors and professionals in the field with the opportunity to update their inspection, monitoring and mitigation strategies. In addition, Inspenet will be present at this international conference, covering the most relevant papers and providing our community with the most outstanding advances in the field of material integrity.

How to Prevent Hydrogen Embrittlement and Stress Corrosion Cracking

Controlling Hydrogen Embrittlement in metallic materials

While it is not possible to completely eliminate the risk of Hydrogen Embrittlement, there are strategies that can significantly reduce its impact and mitigate its effect on metallic materials.

Material selection: The use of steels with low hydrogen permeability, such as austenitic stainless steels, high strength steels with appropriate heat treatment and nickel alloys, is recommended, depending on the specific environmental conditions.

Hydrogen control: It is essential to minimize hydrogen exposure through the use of protective coatings, degassing of materials and control of processes that generate hydrogen, such as electroplating or welding in wet environments.

Heat treatments: The application of post-process heat treatments, such as stress relieving or dehydrogenation at controlled temperatures, can reduce hydrogen accumulation in the material’s microstructure.

Monitoring and early detection: The implementation of non-destructive inspection techniques, such as hydrogen emission spectroscopy, permeation measurement or constant load testing, allows early detection of the presence of hydrogen and prevents catastrophic failures.

Stress Corrosion Cracking Prevention

While it is not possible to completely eliminate the risk of stress corrosion cracking (SCC), there are strategies that can significantly reduce its incidence and mitigate its effects on metallic structures.

Material selection: Materials with high resistance to SCC, such as duplex stainless steels, nickel superalloys and low carbon steels, are recommended. The choice of material should be based on evaluation of the operating environment, concentration of corrosive agents and service temperature.

Environmental control: It is essential to reduce the presence of aggressive species, such as chlorides or sulfates, through the use of corrosion inhibitors, pH control and purification of process fluids. In industrial environments, the application of inert atmospheres can decrease susceptibility to SCC.

Stress relief: The application of post-processing heat treatments, such as stress relief by annealing or mechanical treatments such as shot peening, helps redistribute residual stresses and reduce the risk of crack propagation.

Monitoring and inspection: The implementation of non-destructive inspection (NDT) techniques, such as ultrasonic, eddy current testing and on-line electrochemical monitoring, allows early detection of crack formation and the adoption of corrective measures before structural failure occurs.

This topic will be of particular relevance at the upcoming AMPP Annual Conference + Expo 2025, to be held in Nashville, USA. The event will bring together corrosion and material integrity specialists from around the world, with presentations focused on Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) and hydrogen embrittlement (HE) in critical sectors such as oil, gas and power generation.

Technical discussions will provide engineers, inspectors and structural integrity professionals the opportunity to update inspection, monitoring and failure mitigation strategies. Most importantly, Inspenet will be present covering the highlights of this international conference to share with our community the most relevant developments in the industry.

Conclusions

Hydrogen Embrittlement is due to hydrogen absorption, which reduces ductility and makes the metal more susceptible to stress fracture, while stress corrosion cracking occurs when mechanical stresses and corrosion induce crack growth. Understanding these mechanisms is important to prevent failure in industrial and structural applications through the use of appropriate materials and protective treatments.

In summary, hydrogen embrittlement and stress corrosion cracking are phenomena that affect metals and alloys under specific conditions. Hydrogen Embrittlement is more relevant in materials that absorb hydrogen, reducing their ductility and favoring the formation of cracks, while stress corrosion cracking is due to the interaction between an applied stress and a corrosive environment. Both processes are critical in materials engineering, especially in industries such as aerospace, petrochemical and transportation.

Stress Corrosion Cracking mainly affects metallic alloys, while hydrogen embrittlement can affect both alloys and pure metals such as steel and nickel. Both phenomena require specialized inspections for detection, as the visible effects of stress corrosion cracking are microscopic, and hydrogen embrittlement often goes undetected without detailed material analysis.

References

- Hanson, J.P., Bagri, A., Lind, J. et al. Crystallographic character of grain boundaries resistant to hydrogen-assisted fracture in Ni-base alloy 725. Nat Commun 9, 3386 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05549-y

- pppphttps://www.azterlan.es/kh/fragilizacion-ambiental-por-hidrogeno

- Uhlig, H.H. (1969) An evaluation of stress corrosion cracking mechanisms in Fundamental Aspects of Stress Corrosion Cracking, R.W. Staehle et al. (eds), NACE, Houston, TX.

- Uhlig H. H., Trethewey K. R. and Chamberlain J.,Corrosion Handbook, John Wiley & Sons Inc., 3a. Ed., 1985. 2. Trethewey K. R. and Chamberlain J.

- Nelson, H. G. (1983). Hydrogen embrittlement. In Treatise on Materials Science & Technology (Vol. 25, pp. 275-359). Elsevier.

- Corrosion Monitoring. https://doi.org/10.1533/9781845694050.1.86 Elboujdaini, M., & Revie, R. W. (2009). Metallurgical factors in stress corrosion cracking (SCC) and hydrogen-induced cracking (HIC). Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry, 13(7), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-009-07990

- Pundt, A., & Kirchheim, R. (2006). Hydrogen in metals: microstructural aspects. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res., 36, 555-608.

- Martin, M. L., Dadfarnia, M., Orwig, S., Moore, D., & Sofronis, P. (2017). A microstructure-based mechanism of cracking in high temperature hydrogen attack. Acta Materialia, 140, 300304.