Table of Contents

- Essential metallurgical principles of heat treatment

- Selecting heat treatment according to material and service

- Critical heat treatment variables in plant operations

- Operational checklist for engineers, inspectors, and QA/QC

- Verifying heat treatment: Testing and inspection

- Heat treatment failures: Diagnosis and root causes

- PWHT in critical welds: Application and control

- Standards and industrial requirements for heat treatment

- Practical field cases for industrial heat treatment

- Quick selection and verification checklist

- Mistakes you should avoid

- Conclusions

- References

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Which heat treatment provides better resistance to stress corrosion cracking?

- When is bainite preferable to tempered martensite?

- Which standards define hardness limits in the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ)?

- Which microstructure is more stable at high temperature?

- What factors increase distortion risk during quenching?

- Which process offers better wear/precision balance: carburizing or nitriding?

- What role does heat treatment play in integrity assessment (API/FFS/RBI)?

Heat treatment accompanies metallic materials from their fabrication stage through to their entry into service. While theory presents it through phases, diagrams, and microstructures, in industrial practice it involves decision-making that directly affects performance, safety, and component service life. For a metallurgical engineer or a QA/QC inspector in the Oil & Gas or manufacturing sectors, heat treatment is not merely a metallurgical phenomenon; it is part of an operational workflow that must be specified, controlled, verified, and documented.

This guide is conceived as a practical tool that connects theoretical fundamentals with day-to-day work in the workshop, plant, and field. Its purpose is not to repeat basic classifications of heat treatment processes, but rather to provide selection criteria based on material, service conditions, and initial state; identify critical variables during operation; recognize typical failures and verification routes; and understand how heat treatment interacts with welding, machining, and coating processes.

The final objective is to support professionals who must make technical decisions or supervise execution. Each industry and each component present different challenges, but the principle remains the same: understanding which microstructure is desired, how to obtain it, and how to verify that the result is correct. It is precisely in this convergence between theory and field practice where the true value of heat treatment lies.

Essential metallurgical principles of heat treatment

Transformations and microstructures in steels

Every heat treatment process pursues a metallurgical objective. Quenching, tempering, annealing or austempering are not arbitrary operations; they are controlled routes designed to achieve a specific combination of phases and grain sizes. In steels, the fundamental microstructures are austenite, ferrite, pearlite, bainite and martensite. Each one shapes the mechanical behavior of the material and its performance in service.

When heating above the critical region, austenite forms. This phase exhibits higher carbon solubility and serves as the starting point for most transformations. From that point on, cooling rate and time dictate the microstructural outcome. Slow cooling favors ferrite and pearlite (more ductile microstructures), while more severe cooling rates can lead to bainite or martensite. Martensite is formed by a diffusionless transformation; it is hard but brittle and requires tempering to balance its properties.

Austempering, martempering, and other intermediate processes aim to produce more stable bainitic structures with lower distortion tendencies. At its core, any heat treatment strategy seeks to reach the right microstructure for the intended service conditions.

TTT/CCT curves and their impact on thermal processing

TTT (Time-Temperature-Transformation) and CCT (Continuous-Cooling-Transformation) curves map how a steel microstructure evolves under different combinations of time and temperature. While they may appear to be academic tools, in workshops and industrial plants they guide critical decisions: which quenching medium to use, what level of severity is acceptable, and which alloy can tolerate a given thermal profile.

For steels intended for quenching, these curves define the window in which martensite can be obtained without passing through ferrite-pearlite. In isothermal processes such as austempering, the curves allow the material to “reside” in regions favorable to bainite formation. In martempering, they help reduce thermal gradients and, consequently, distortion and residual stress. The choice of quenching medium, water, oil, polymer or air, and the geometry of the part must be evaluated with these curves in mind. Ignoring them in industrial applications leads to incomplete microstructures, off-spec hardness, and, in the worst cases, premature failures.

Microstructure and properties in industrial service

The ferrite-pearlite combination favors ductility and cold workability, supporting forming, bending, and fabrication processes. These microstructure-property relationships underpin any metallurgical decision: before discussing procedures, the target microstructure must be defined. For an extended explanation of this microstructure-property relationship.

Selecting heat treatment according to material and service

Heat treatment selection based on material

The material defines the range of viable treatments. In carbon and alloy steels, common in Oil & Gas, structural components, and machinery, traditional quench and temper (Q&T) routes allow hardness, strength, and toughness to be tailored. In applications dominated by fatigue and wear, Q&T remains the most balanced approach. In alloy steels containing Cr, Mo, and Ni, cooling severity can be reduced thanks to improved hardenability, enabling less aggressive quench media (oil or polymers) with lower distortion risk.

Stainless steels require a different strategy. Here, corrosion and temperature resistance are often the primary concerns. Solution treating and, in certain series, aging is used to recover toughness, dissolve carbides, and minimize sensitization in regions exposed to intergranular attack. Martensitic stainless grades can be quenched and tempered for mechanical applications, provided temper embrittlement is respected.

Tool steels, used for molding, cutting, and die operations, rely on quench + temper cycles to achieve high surface hardness and thermal stability. The choice of quench medium and tempering control is decisive to prevent cracking and in-service softening.

In aluminum and titanium, the strength-to-weight ratio dictates the treatment. Solution treating and aging (natural or artificial) are typical for aluminum; in titanium, heat treatment adjusts the α–β proportion to balance strength, toughness, and creep resistance. In aerospace and precision-critical components, cryogenic treatments may complement conventional cycles to enhance dimensional stability.

Heat treatment selection based on service conditions

When service demands wear or abrasion, valves, seats, rotary equipment, tempered martensite, and carburizing are common solutions. If the component operates under impact, hammers, mechanisms, machinery parts, bainitic structures, or Q&T combinations offer a better blend of hardness and toughness.

For components subjected to mechanical or thermal fatigue, shafts, springs, rods, bainitic or tempered martensitic microstructures are more predictable, where defect sensitivity and microstructural stability become critical. In corrosion + temperature environments, refineries, petrochemical plants, power generation, stainless alloys with solution treatment, and, in some grades, aging are preferred; in ferritic and martensitic steels, tempering ranges that promote embrittlement must be avoided.

For creep and high-temperature service, boiler tubes, furnaces, heat exchangers, and turbines, alloys engineered for precipitation strengthening or thermo-stable behavior are employed. In such cases, heat treatment does not seek hardness alone, but long-term stability and resistance to slow deformation.

Heat treatment based on the initial condition of the part

In cast components, heat treatment must account for porosity, segregation, and grain size. Annealing or normalizing can homogenize microstructures before machining. In forged and rolled parts, fiber direction and residual stresses matter; here, Q&T aligns properties with the required loading direction.

If machining was performed before heat treatment, distortion and induced stress should be evaluated; intermediate stress-relief cycles can reduce rejection rates. In welded components, the HAZ concentrates stresses and microstructural variations. PWHT becomes a key tool to lower hardness and improve toughness. In short: if cast → homogenize; if forged/rolled → Q&T; if machined → relieve; if welded and critical → evaluate PWHT.

Critical heat treatment variables in plant operations

Temperature and time in heat treatment

Temperature defines the metallurgical phase available, and time allows the transformation to be completed. In steels intended for quenching, heating above the critical point promotes the formation of austenite, the phase required to obtain martensite during cooling. There is no need to operate “hotter” than required; overheating induces grain growth, loss of toughness, and a higher tendency to crack during service. Underheating, on the other hand, produces incomplete microstructures and hardness levels below specification.

Time at temperature must be sufficient to homogenize and allow carbon diffusion, without prolonging it to the point of grain coalescence or undesirable precipitation. In stainless steels or precipitation-sensitive alloys, time control becomes as important as the thermal range, especially when corrosion resistance depends on avoiding carbide formation at grain boundaries. In annealing or normalizing cycles, the objective is to relieve internal stress and refine microstructure, not simply reach a target temperature.

Cooling media and cooling rate

Cooling determines the severity of the treatment and the resulting microstructure. Water is the most severe medium, followed by polymers and oils, while air and furnace cooling represent moderate or slow rates. Salt baths and other isothermal media allow controlled transformations that avoid excessive martensite and distortion, as seen in austempering and martempering.

Higher cooling severity increases hardness but also raises the risk of cracking and distortion, particularly in parts with abrupt section changes. In alloy steels with high hardenability, oil or polymer quenching are preferred to avoid severe residual stresses. In critical components such as pumps, valves or mechanisms, changing the quenching medium implies changing process severity, a modification that should never be made without requalifying the cycle. Geometry and thickness dictate the selection: thin parts tolerate faster media; massive parts require gradual control to avoid extreme thermal gradients.

Furnace atmosphere, decarburization, and surface oxidation

The furnace atmosphere affects the surface of the part. In precision components, gears, bearings, and valves, decarburization reduces surface hardness and alters dimensional fits. Oxidation increases post-processing and may compromise critical tolerances. Controlled atmospheres or protective gas furnaces are advisable when surface contact, wear, or thermochemical treatments such as carburizing or nitriding are required.

Distortion and stresses in treated parts

Distortion stems from thermal gradients and complex geometries: uneven sections, holes, threads, and abrupt transitions favor warping. Residual stresses increase when cooling is severe or fixturing restricts deformation. These variables affect subsequent operations such as machining, grinding, and final fitting, where scrap and rework represent high production costs.

Operational checklist for engineers, inspectors, and QA/QC

Before heat treatment

The pre-treatment stage determines whether the process will begin under controlled conditions. The first step is to verify the material through certificates and traceability; it is not only about confirming the alloy, but also its initial condition (rolled, forged, cast, or welded). Geometry must be reviewed to identify critical areas: section changes, holes, fillets, and threads are candidates for distortion and stress concentration. Surface cleanliness is essential; oxides, contaminants, or coatings can affect heat transfer and quenching performance.

If welds are present, the HAZ should be inspected and the need for PWHT evaluated. Finally, the procedure (WPS/PTS) is validated to ensure that the thermal cycle, quenching medium, and instrumentation align with customer specifications and the applicable code.

During heat treatment

At this stage, the variables that dictate the final microstructure are controlled. Heating ramps must follow the procedure to avoid violent thermal gradients that may induce cracking or undesired phase transformations. Thermocouples require proper calibration and positioning; inadequate recording invalidates the cycle in audits or certifications. Furnace temperature uniformity is critical in massive parts or complex geometries, where small variations affect hardness and distortion.

Holding time must be sufficient to complete diffusion or transformation without prolonging it unnecessarily. During cooling, the medium, temperature, agitation, and severity are controlled, and any deviations that may affect final quality are documented.

After heat treatment

Immediate hardness checks must be performed and, when applicable, surface or case microhardness. Visual inspection detects distortion, cracking, decarburization, or quench marks. Dimensional inspection is essential in interference-fit or precision components; minimal deviation can invalidate an entire batch. Finally, documentation for QA/QC is consolidated: thermal parameters, heating curves, media used, test results, and traceability. This record supports audits, certifications, and future failure analysis.

Verifying heat treatment: Testing and inspection

Direct testing of properties and microstructure

The first verification after heat treatment is hardness, typically measured using Rockwell, Brinell, or Vickers scales depending on component type and sensitivity requirements. Hardness provides a fast reading of the metallurgical result and, in many critical parts, serves as a contractual acceptance criterion. In carburized or nitrided components, microhardness is essential to evaluate case depth and surface gradient; insufficient case thickness or an abrupt transition may compromise wear resistance or fatigue performance.

Metallography complements these tests and confirms the phases present, carbide distribution, grain size and transformation quality. For components subjected to thermochemical processes, continuity, and uniformity of the hardened layer are also evaluated. In special situations, such as components carrying high residual stresses or operating under critical service conditions, X-ray diffraction may be used to quantify residual stresses and correlate them with cracking or distortion risk. Together, these tests provide a reliable picture of the metallurgical performance of the treatment.

Indirect testing and service performance

In critical projects, impact testing (Charpy) verifies material toughness under dynamic loads or low-temperature conditions, common in piping or vessels subjected to thermal fluctuations. Fatigue, mechanical or thermal, is evaluated when the component will experience cyclic loading, such as pump shafts, springs, or parts exposed to repeated starts and shutdowns in industrial plants. In wear-dominated applications, abrasion or erosion tests allow comparison of alternative treatments and validation of pilot cycles before full-scale production. These tests are not always part of routine control but are decisive for reliability assessment and service life estimation.

Acceptance criteria in Oil & Gas and manufacturing

In regulated sectors, acceptance criteria typically focus on target hardness ranges, case depth, and uniformity of micro treatment. In welded zones, hardness limits are established to mitigate hydrogen-induced cracking. Final acceptance combines customer specifications, applicable codes, and documentary evidence for audits.

Heat treatment failures: Diagnosis and root causes

Quenching failures: Typical defects

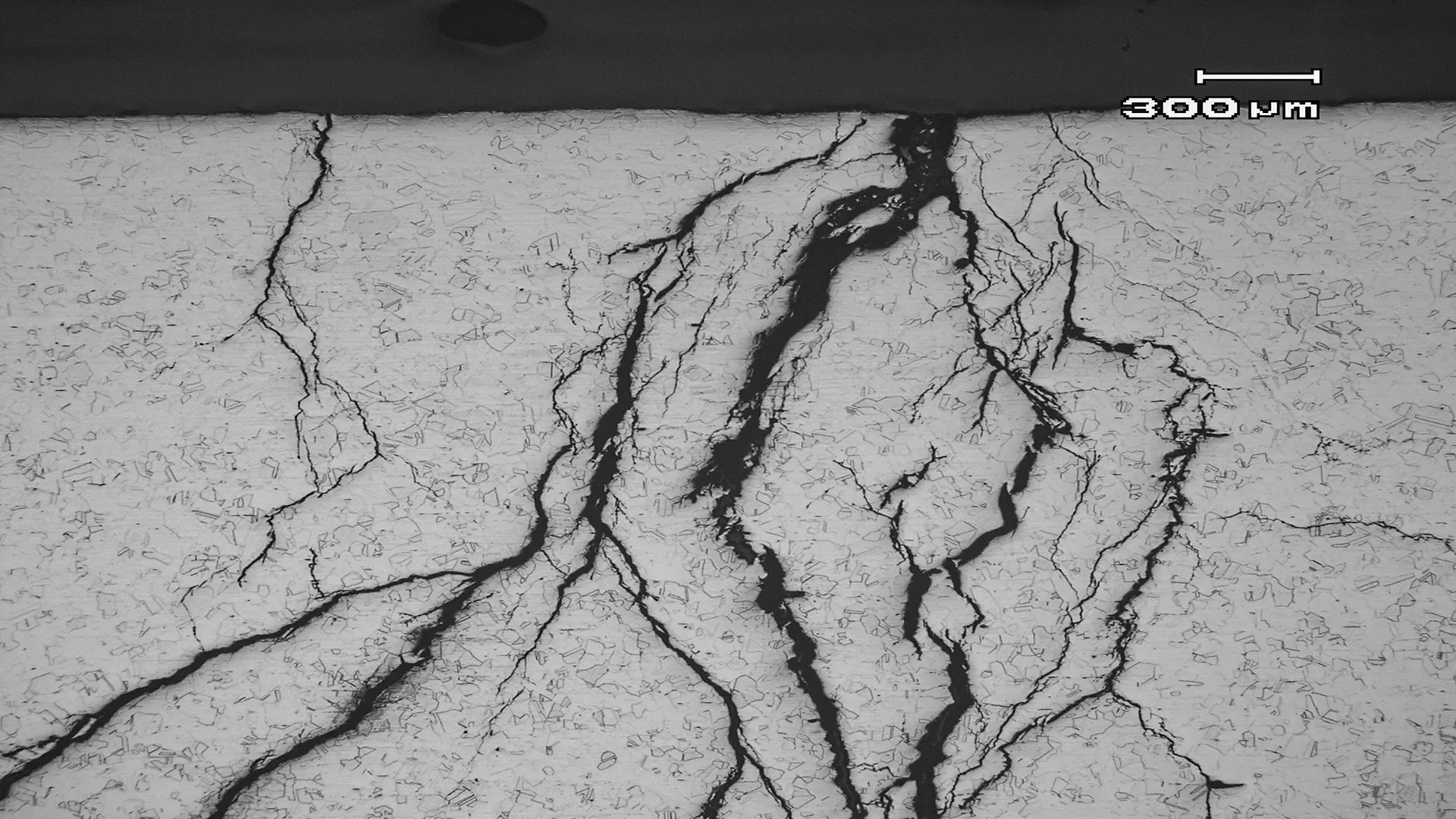

Quench cracking appears when cooling severity exceeds the material’s ability to accommodate stress; it may also originate from pre-existing defects or from designs with abrupt section changes. Excessive distortion is common in unbalanced geometries, holes, or threads, where thermal gradients promote differential deformation. Lack of hardness occurs when cooling does not pass through the martensitic region or when the steel’s hardenability is insufficient for the section being treated. In all cases, root causes can often be traced to quenching medium selection, incorrect austenitizing temperature, or overlooked geometric features.

Tempering issues: Embrittlement and hardness loss

Improper tempering can produce two opposite problems. Tempering within sensitive ranges may induce embrittlement, reducing toughness and promoting brittle fracture. Over-tempering, on the other hand, lowers hardness below specified requirements, compromising wear or fatigue resistance. In both cases, thermal records and temperature control are essential for diagnosis.

Annealing and normalizing problems

Excessive grain growth reduces toughness and may require retreatment. Surface decarburization affects fit and wear performance. Insufficient mechanical properties often indicate inadequate temperatures or times, or lack of homogenization.

Failures associated with welding and PWHT

Hydrogen-induced delayed cracking is frequent in weldments with high hardness in the HAZ. PWHT mitigates this risk by reducing residual stress and hardness. Excessive hardness in the HAZ and embrittlement from poorly executed treatments accelerate in-service failures and compromise structural integrity.

PWHT in critical welds: Application and control

When to apply PWHT in pressure equipment

Post Weld Heat Treatment (PWHT) is applied when the combination of material, thickness, and service introduces the risk of residual stresses, embrittlement, or cracking. In high-pressure piping and pressure vessels, stress accumulation can accelerate failure mechanisms under load or thermal cycling. In refineries and petrochemical plants, PWHT becomes critical for joints involving Cr-Mo materials, quenched and tempered alloy steels, and welded sections exposed to corrosive environments or elevated temperatures.

Design and fabrication codes (ASME, API, AWS, and others) commonly state when PWHT is mandatory based on thickness, alloy, and service conditions. In EPC projects and turnaround outages, these requirements are integrated into the WPS and verified through QA/QC audits. For components not subject to pressure but critical in operation (flanges, nozzles, transitions, and load-bearing regions), technical judgment may justify PWHT even when not explicitly required by the code.

As a complementary resource, an educational video on post-weld heat treatment is available on the Heat Treatment Page (YouTube). In the video, the presenter, identified as Jamie, offers a concise overview of stress-relief, normalization, hardening, and tempering methods as applied to welded joints. This audiovisual material reinforces the fundamentals of PWHT without replacing formal code requirements established by ASME, API, and AWS.

Key PWHT parameters

PWHT consists of heating to a specified temperature range for a minimum hold time to allow stress relaxation and partial transformation of hardened microstructures. Temperature and hold time are selected according to steel grade and joint thickness; thicker sections require longer ramps and holds to ensure temperature uniformity.

Heating by electrical resistance or thermal blankets demands controlled rates and monitoring with thermocouples. The cooling stage must be gradual to prevent re-inducing stress or distortion. In Cr-Mo materials or quenched and tempered alloys, poorly executed PWHT may alter creep strength or induce precipitation embrittlement.

Risks of improper PWHT execution

PWHT performed out of specification (poorly designed or poorly executed) may reduce strength and toughness, generate distortions, or align stresses in unintended regions. It may also trigger in-service failures if microstructure is altered or if the final hardness exceeds acceptable limits. In Oil & Gas operations, such errors translate into loss of integrity and operational risk.

Standards and industrial requirements for heat treatment

When heat treatment is part of a fabrication or repair cycle, it is not executed solely on metallurgical criteria; it is governed by standards and specifications that define requirements for hardness, microstructure, PWHT, and documentation.

In Oil & Gas and manufacturing, ASME, API, and AWS codes establish conditions for critical welds, pressure vessels, and piping, including when PWHT is mandatory and which hardness values must not be exceeded to prevent hydrogen-induced cracking or embrittlement. ASTM and ISO provide test methods for hardness, metallography, and material characterization, while AMS and NADCAP govern aerospace processes with stricter traceability and statistical process control.

For the engineer or inspector, the impact is direct: hardness is not only a metallurgical indicator but also a contractual acceptance criterion. Thermal records, temperatures, ramps, hold times, and cooling, must be retained in reports and certificates, as they form part of the evidence required in audits and verification activities. Documentation ensures the component not only achieved the intended properties but did so under a qualified and repeatable procedure. In this regulated environment, meeting specifications also means meeting safety and operational reliability expectations.

When to apply each standard in heat treatment

1. ASME: Codes for pressure equipment

When it applies:

- Fabrication, repair, and alteration of pressure vessels, heat exchangers, boilers, piping, and pressurized systems.

- In refineries, petrochemical plants, power generation, and industrial facilities.

What it covers:

- Mechanical design

- Material selection

- Welding and PWHT requirements

- Testing and acceptance

- Certification and stamps

Impact on heat treatment:

- Defines when PWHT is mandatory based on thickness + material + service.

- Establishes hardness and HAZ limits.

- Requires qualification of procedures (WPS/PQR) and full traceability.

Where does NOT apply:

- Components are not subject to pressure or without structural integrity relevance.

2. API: Integrity and operations in Oil & Gas

When it applies:

- Tanks, piping, refineries, terminals, inspection, and maintenance.

Relevant examples:

- API 570 (piping)

- API 510 (pressure vessels)

- API 653 (tanks)

- API 579 (FFS / Fitness-for-Service)

- API 6A/16A (wellhead and drilling equipment)

Impact on heat treatment and welding:

- Introduces criteria for maximum hardness, HAZ control, and PWHT.

- Provides the basis for integrity assessments (RBI/RBA).

Where does NOT apply:

- Pure fabrication stages without operational relevance.

3. AWS: Welding and qualification standards

When it applies:

- Qualification of welders, procedures, and consumables.

Metallurgical impact:

- Defines how PWHT is qualified within the PQR.

- Controls post-weld hardness and HAZ behavior in hardenable steels.

Where does NOT apply:

- In-service performance and lifecycle integrity (covered by API).

4. ASTM/ISO: Test methods and material characterization

When it applies:

- Laboratory controls, QA/QC and material reception.

Direct metallurgical impact:

- Defines how to measure hardness, perform metallography, evaluate case depth and prepare specimens.

Role in heat treatment:

- Enables verification and documentation that heat treatment achieved the intended microstructure and hardness.

Where does NOT apply:

- Structural integrity decisions, design, or operational criteria.

5. AMS + NADCAP: Aerospace and critical manufacturing

When they apply:

- Aerospace, defense, industrial turbines, precision manufacturing, and mission-critical components.

Real impact:

- Heat treatment must not only be done correctly; it must be reproducible, traceable, and auditable.

- Statistical control + furnace validation + lot documentation.

Where they do NOT apply:

- General industry or non-aerospace Oil & Gas (although some high-end plants adopt NADCAP as a quality benchmark).

How standards integrate across the industrial cycle

A practical way to understand how these standards interact is to map them across the phases of the industrial cycle:

| Fase | Norma dominante |

| Design | ASME / API |

| Materials | ASTM / ISO |

| Welding | AWS / ASME IX |

| PWHT | ASME / API / AWS |

| Testing | ASTM / ISO |

| Operation / Integrity | API / FFS / RBI |

| Audit / Excellence NADCAP / AMS (depending on industry) | Audit / Excellence NADCAP / AMS (depending on industry) |

Practical field cases for industrial heat treatment

Case 1: Valve component in a refinery

A gate valve manufactured from alloy steel exhibited premature wear on the seat due to particulate contamination and turbulent flow. A quench & temper cycle was selected to increase hardness and improve wear resistance while maintaining sufficient toughness to prevent brittle fracture. Post-treatment hardness checks confirmed compliance with the contractual range and stability of the mating surface.

Case 2: Pump shaft subjected to fatigue in a chemical plant

A pump shaft experienced thermal and mechanical fatigue cracking after repeated start-up cycles. The original cycle was replaced with a bainitic heat treatment that provided a more favorable balance between strength and toughness. The service life increased significantly, reducing maintenance interventions and improving stability under continuous operation.

Case 3: Welded joint in high pressure piping

During a field repair, a pipe operating at high pressure and temperature required PWHT to reduce residual stresses and prevent delayed hydrogen cracking. Hardness levels in the HAZ were checked, and full traceability of the thermal cycle was documented. The joint was accepted according to specification and returned to service without objections.

Case 4: Transmission gears in a manufacturing line

Carbon steel gears intended for continuous service displayed accelerated wear during production start-up. Carburizing followed by tempering was implemented to harden the surface without compromising core toughness. Case depth was verified by microhardness testing, preventing brittle failures and ensuring proper fit with the mating shaft.

Case 5: Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) in a critical component in service

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) results from the combined action of an aggressive environment and residual or applied stresses, producing intergranular or transgranular cracking depending on the material and chemical conditions (Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)). In Oil & Gas, SCC frequently appears in systems exposed to chlorides, amines, CO₂, or H₂S, where the material–environment–stress interaction accelerates degradation and compromises structural integrity.

In this case, a carbon steel component developed SCC during continuous operation; residual stresses originated from welding and insufficient heat treatment, while chlorides acted as the environmental trigger. The assessment was performed under API 579/FFS to determine severity, remaining life, and corrective actions. Metallographic examination confirmed branched cracking consistent with SCC, validating the damage mechanism and supporting intervention. Such metallographic evidence is essential to close the diagnostic loop and adjust heat treatment specifications, allowable stresses, and RBI strategies to prevent recurrence.

Quick selection and verification checklist

If the service requires… → Consider heat treatment…

| Service Requirement | Possible Metallurgical Solution |

| Severe wear / abrasion | Quench & Temper / Carburizing |

| Dimensional stability / precision | Quench + Cryogenic + Temper |

| High pressure + High temperature | Normalizing + Tempering / Code-defined cycles |

| Mechanical or thermal fatigue | Bainitic or Tempered Martensitic (as required) |

| Critical weldment | Evaluate PWHT based on material + thickness + code |

| Corrosion + temperature | Solution Treatment / Aging (stainless and specialty alloys) |

This table does not replace a specification; it guides preliminary decision-making and avoids metallurgical routes that are incompatible with the material or the service environment.

Mistakes you should avoid

- Changing the quench medium without requalifying the procedure (severity is not a minor detail).

- Accepting components solely based on hardness without confirming microstructure or case depth (carburized and nitrided parts often fail here).

- Performing PWHT without verifying material, thickness, or code requirements; in some steels it may induce embrittlement.

- Omitting thermal records or traceability: if it isn’t documented, it technically “does not exist.

- Heat treating machined components without assessing distortion risk; rework may exceed the cost of the treatment.

- If one treatment improves “everything,” it optimizes certain properties while sacrificing others; always define the target microstructure first.

Conclusions

Heat treatment is often explained in theoretical terms, yet its true impact is defined in the plant, in the shop, and in the field—where each component must perform under real operating conditions. Selecting the correct thermal cycle requires understanding the material, the design, the process demands, and the constraints of the operating environment. Verification demands testing, measurement, documentation, and acceptance based on technical criteria, because in Oil & Gas and manufacturing a metallurgical error is rarely harmless; it compromises performance, reliability, and in some cases, safety.

This guide is not intended to exhaust a broad and demanding subject. Its purpose is to provide a practical path that connects microstructure, service conditions, and quality control. If it helps an engineer, inspector, or QA/QC professional specify a more suitable heat treatment, avoid distortion, interpret hardness values correctly, or justify a PWHT requirement, it will have fulfilled its objective.

As the author, I hope that this material becomes a useful day-to-day reference. If it prompts further questions or encourages deeper exploration, it is even better: in metallurgy, the best decisions often begin with a well-framed question.

References

- Krauss, G. (1990). Steels: Heat treatment and processing principles. ASM International.

- Davis, J. R. (Ed.). (1991). ASM handbook, volume 4: Heat treating. ASM International.

- Callister, W. D., & Rethwisch, D. G. (2020). Materials science and engineering: An introduction (10th ed.). Wiley.

- ASTM International. (2021). ASTM E18: Standard test methods for Rockwell hardness of metallic materials.

- American Petroleum Institute. (2016). API 579-1/ASME FFS-1 Fitness-for-service.

- American Welding Society. (2015). AWS D1.1/D1.1M: Structural welding code—steel.

- Inspectioneering Journal. (2025). Risk-based inspection and PWHT considerations in Oil & Gas operations.

- Staehle, R. W. (2007). Stress corrosion cracking: Materials performance limits. Corrosion, 63(7), 603–622.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Which heat treatment provides better resistance to stress corrosion cracking?

In quenched and tempered steels, stress corrosion cracking tends to worsen with high hardness and elevated residual stress. Bainitic and tempered martensitic structures with controlled hardness can reduce susceptibility by improving stress distribution. In stainless steels, solution annealing and controlled aging can improve resistance in chloride environments and at elevated temperatures.

When is bainite preferable to tempered martensite?

The choice depends on the balance between strength, toughness, and fatigue behavior. Bainite is advantageous when cyclic loading dominates, and crack initiation must be delayed. Tempered martensite is preferred when hardness and wear resistance are primary drivers, provided tempering avoids embrittlement.

Which standards define hardness limits in the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ)?

In Oil & Gas, ASME, API, and AWS establish hardness limits to prevent hydrogen cracking and maintain toughness. API 570/510/653 and relevant ASME sections for pressure equipment and piping define maximum hardness based on alloy and thickness. AWS D1.x provides criteria for structural welds.

Which microstructure is more stable at high temperature?

Microstructures with stable carbides and low solubility tend to resist creep deformation. In Cr-Mo steels and high-temperature alloys, tempered bainite and tempered martensite can offer dimensional stability and creep resistance depending on temperature range.

What factors increase distortion risk during quenching?

The main contributors are unbalanced geometry, steep thermal gradients, mixed thick-thin sections, high cooling severity, and lack of design allowances. Pre-existing residual stress can amplify distortion effects.

Which process offers better wear/precision balance: carburizing or nitriding?

Carburizing produces deep hardened cases suitable for gears and power transmission. Nitriding yields shallower but more dimensionally stable cases, ideal for precision components in continuous service. Selection depends on case depth requirements and tolerances.

What role does heat treatment play in integrity assessment (API/FFS/RBI)?

Heat treatment influences mechanisms such as fatigue, creep, stress corrosion cracking, and embrittlement, all of which are evaluated in API 579-based Fitness-for-Service and RBI frameworks. Inadequate microstructures can accelerate damage mechanisms and reduce remaining life.