Table of Contents

- Mathematical foundations: Probabilistic modeling of failure

- How do systems behave across the life cycle?

- Predictive maintenance: Towards reliability engineering

- Continuous monitoring transforming maintenance

- Failure mode analysis in risk identification

- Trends: Artificial intelligence and digital twins

- How does sustainability impact reliability?

- Regulations & standards for critical industries

- Autonomous systems & adaptive reliability

- Conclusion

- References

Reliability engineering is a multidisciplinary discipline that integrates principles of probability theory, statistical analysis, and optimization methods to quantify, predict, and improve the performance of technical systems under real operating conditions.

This technical specialization transcends the traditional concept of quality by incorporating the temporal dimension as a fundamental variable, allowing us to evaluate not only whether a component or system is functioning correctly, but also how long it will maintain its functionality within specified parameters.

The conceptual origin of this discipline dates back to the pioneering work of Waloddi Weibull in the 1950s, who developed the statistical distribution that bears his name to model failure times in bearings. Subsequently, the US aerospace and military industries expanded on these fundamentals, establishing the MIL-STD standards that would eventually evolve into contemporary regulatory frameworks such as IEC 61508 and ISO 14224, which is an international standard dealing with the collection and exchange of reliability and maintenance data for equipment in the process industry.

Mathematical foundations: Probabilistic modeling of failure

The rigorous quantification of reliability is based on mathematical constructs that describe the random behavior of failures. The reliability function R (t) expresses the probability that a system will operate without failure during a defined time interval, formulated mathematically as

R(t) = P (T > t), where T represents the random variable describing the time to failure. This function exhibits monotonically decreasing properties, starting at

R (0) = 1 and converging asymptotically to zero as t tends to infinity.

The instantaneous failure rate, designated by the hazard function λ(t), is another fundamental descriptor that characterizes the propensity to fail as a function of cumulative operating time.

This metric is defined as the limit of the conditional probability of failure in an infinitesimal interval, expressed mathematically as λ(t) = f(t) / R(t), where f(t) represents the probability density function of the time to failure. The relationship between these functions allows us to establish that R(t) = exp[-∫λ(τ)dτ], providing a cohesive theoretical framework for predictive analysis.

How do systems behave across the life cycle?

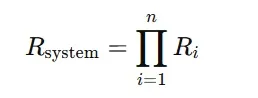

The topological configuration of components within a system fundamentally determines its aggregate reliability. Series systems, where the failure of any component causes the entire system to fail, exhibit total reliability:

where RiR_iRi is the reliability of each component. In this configuration, the system’s reliability is constrained by the least reliable components, representing the most unfavorable case from an operational availability perspective.

In contrast, parallel systems implement active redundancy: multiple components perform the same function simultaneously, and the system only fails if all components fail, significantly increasing operational resilience.

k out of n systems, where at least k of n components must operate correctly, allow reliability to be adjusted according to availability requirements and economic constraints, using the cumulative binomial distribution for calculation.

In practice, systems rarely have purely series or parallel topologies. Therefore, advanced techniques such as reliability block diagrams (RBDs), fault tree analysis (FTA), and Markov diagrams are employed to model complex architectures with functional dependencies, common failure modes, dynamic reconfiguration, and changes in reliability across the system life cycle, including wear, maintenance, and upgrades.

Predictive maintenance: Towards reliability engineering

The maintenance strategy is a fundamental lever for maximizing operational availability while minimizing life cycle costs. Corrective or reactive maintenance, historically implemented in most industrial facilities, operates under the paradigm of post-failure intervention, resulting in unpredictable downtime and high operating costs due to secondary catastrophic failures and production losses.

Age- or calendar-based preventive maintenance implements scheduled interventions at fixed intervals regardless of the actual condition of the equipment.

Optimizing the maintenance interval requires balancing the cost of premature interventions against the risk of failures between intervals, typically formulated as a problem of minimizing the expected cost per unit of operating time using renewal theory.

Continuous monitoring transforming maintenance

Condition-based maintenance (CBM) and its evolution towards predictive maintenance represent the current technological frontier, leveraging advanced sensors and signal processing algorithms to quantify the health status of critical components using measurable degradation indicators.

Techniques such as vibration analysis using Fourier transforms and wavelets, infrared thermography, oil analysis using spectrometry, and partial discharge monitoring in electrical assets allow failure precursors to be detected early enough to plan optimized interventions.

Mathematical modeling of CBM typically uses stochastic processes such as gamma degradation models or Brownian motion with drift to describe the temporal evolution of the health indicator, establishing alert and alarm thresholds using optimization techniques that consider the costs of false positives (unnecessary intervention) versus false negatives (undetected failure).

The expected value of the optimal replacement time is determined using stochastic dynamic programming or rolling horizon algorithms.

Failure mode analysis in risk identification

FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) is a structured bottom-up technique for systematically identifying potential failure modes, their root causes, and their effects on system performance.

This methodology, which originated in the aerospace sector through MIL-STD-1629, has expanded to virtually all industrial sectors, evolving into specialized variants such as FMECA (incorporating quantitative criticality) and DFMEA (design-oriented).

The FMEA process examines each functional component, identifying its characteristic failure modes, determining the physical mechanisms causing them through stress, degradation, or operational error analysis, evaluating local and systemic effects, and finally establishing preventive or detective controls.

The prioritization of corrective actions is based on the Risk Priority Number (RPN), calculated as the product of severity, occurrence, and detectability, although contemporary methodologies such as FMEA according to VDA/AIAG have introduced more sophisticated action prioritization matrices.

Trends: Artificial intelligence and digital twins

Reliability engineering is being transformed by artificial intelligence (AI) and digital twins, key technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. AI algorithms, including deep neural networks and survival models such as the Cox Proportional Hazards Model with neural embeddings, enable the identification of complex degradation patterns from multivariate sensor data, without relying on traditional physical modeling.

Digital twins create virtual replicas of physical assets that evolve in real time through continuous integration of operational data. They combine multiphysics models, stochastic differential equations, and Bayesian algorithms to accurately update each asset’s remaining useful life (RUL).

Thanks to these technologies, it is possible to perform individualized asset forecasting, taking into account operational history and specific environmental conditions. This approach surpasses the limitations of traditional population-based models and enhances predictive maintenance optimization and advanced reliability.

How does sustainability impact reliability?

The growing imperative of environmental sustainability is redefining optimization objectives in reliability engineering. The traditional concept of maximizing operational availability must be balanced with minimizing carbon footprint, energy consumption, and waste generation throughout the life cycle.

This multi-dimensionality requires multi-objective optimization frameworks using Pareto frontier techniques or weighted utility functions that reflect organizational preferences regarding trade-offs between availability, cost, and sustainability.

Life cycle analysis (LCA) integrated with reliability engineering allows for the quantification of environmental impacts not only from production and final disposal, but also from maintenance interventions, spare parts consumption, and operational energy, considering the uncertainties inherent in the stochastic useful life of components. Emerging methodologies such as eco-Reliability seek to design systems that simultaneously optimize intrinsic reliability and minimize environmental degradation.

Regulations & standards for critical industries

The development and operation of systems in regulated sectors requires compliance with international standards that codify best practices in reliability engineering. The IEC 61508 standard establishes functional safety requirements for electrical, electronic, and programmable electronic systems, defining safety integrity levels (SIL) from SIL 1 to SIL 4 with progressively stringent requirements for probability of failure on demand, typically ranging from 10^-2 to 10^-5 per hour of operation.

Specific sectors have developed specialized adaptations such as IEC 61511 for the process industry, ISO 26262 for automotive systems, and EN 50126/50128/50129 for railway applications, each incorporating particular requirements reflecting the risk characteristics and consequences of failure in their domain.

Demonstration of compliance with these standards requires documented evidence through quantitative reliability analyses, verification and validation plans, and complete traceability from requirements to implementation.

Autonomous systems & adaptive reliability

Contemporary autonomous systems, from autonomous vehicles to collaborative robots and smart energy management systems, present unprecedented challenges for reliability engineering.

The incorporation of artificial intelligence algorithms introduces elements of randomness and emergent behavior that challenge traditional deterministic paradigms of safety analysis.

The concepts of adaptive reliability and self-diagnostic and self-repairing architectures (self-healing systems) represent emerging paradigms where systems not only detect degradation but also autonomously implement reconfiguration or parametric adjustment strategies to maintain acceptable performance in the face of incipient failures.

The mathematical formalization of these adaptive behaviors using stochastic optimal control theory and observable Markov decision processes is an active area of research with profound implications for the next generation of resilient technical systems.

Conclusion

The integration of artificial intelligence and digital twins represents a major advancement for reliability in modern engineering. These technologies enable individualized asset life forecasts, optimize predictive maintenance, and transform traditional population-based models into adaptive and precise systems. Consequently, reliability becomes not a static goal but a dynamic process, grounded in real data and advanced analytics, ensuring safer, more efficient, and resilient operations.

References

- ISO 14224:2016: https://www-iso-org.

- Mao, R., Wan, L., Zhou, M., & Li, D. (2025). Cox-Sage: Enhancing Cox proportional hazards model with interpretable graph neural networks for cancer prognosis. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 26(2), bbaf108. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaf108

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii