Table of Contents

- What is Fracking and what is it used for?

- CO₂: Fracturing technology

- API Standards: Safety and environmental responsibility

- Hydraulic fracturing: Well integrity

- What advances define modern fracking?

- Electrification transforming operational emissions

- Gas compressors vs diesel fuel in fracking

- How is the water challenge managed efficiently?

- Automation that maximizes operational precision

- Advanced microseismic monitoring technologies

- What is the future of sustainable fracking?

- Conclusions

- References

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Hydraulic fracturing, known worldwide as fracking, continues to be one of the most debated topics in the global energy industry. But beyond the controversy, what technological advances are transforming this practice and making it more sustainable?

What is Fracking and what is it used for?

Fracking is an extraction technique that consists of injecting high-pressure water mixed with sand and chemical additives into underground rock formations to fracture them and release trapped hydrocarbons, mainly natural gas and oil.

This technology transformed the energy industry by enabling access to unconventional reservoirs that were previously technically inaccessible. Thanks to fracking, the United States shifted from being a net energy importer to becoming one of the world’s leading producers of natural gas and oil.

Natural gas extracted through fracking is used for electricity generation, industrial and residential heating, and as a feedstock for the petrochemical industry. Its application has helped reduce dependence on more polluting fuels such as coal in several countries.

CO₂: Fracturing technology

As unconventional oil and gas have gained increasing attention, the application of waterless fracturing technology, represented by carbon dioxide (CO₂) fracturing, in the development of unconventional oil and gas resources presents broad prospects.

CO₂ fracturing technology offers several advantages, such as low formation damage and easy flowback. It is particularly suitable for complex rock strata with low pressure, low permeability, and high water sensitivity. In addition, this technology has a positive impact on reservoirs with low water content and high contamination.

Results indicate that CO₂ fracturing can stimulate unconventional reservoirs more effectively than conventional hydraulic fracturing, demonstrating high technical feasibility and potential application in future reservoir stimulation and redevelopment.

API Standards: Safety and environmental responsibility

API RP 100-1 and 100-2 are standards issued by the American Petroleum Institute (API) that provide guidance for shale development, focusing on well integrity, fracture containment, environmental protection, waste management, emissions reduction, site planning, and workforce training.

The standard is based on three key principles: integrity, safety, and environmental responsibility, while also guiding effective communication with the community.

API RP 100-1 and 100-2

- Shale development: These standards provide guidelines for the safe and responsible development of shale projects, including drilling and hydraulic fracturing.

- Well integrity and containment: They establish recommendations to ensure pressure containment and well integrity to prevent leaks.

- Environmental protection: They offer guidance on waste management, emissions reduction, groundwater protection, and site planning.

- Training and safety: They include guidelines for training workers involved in operations.

- Communication: The standard emphasizes the importance of open and effective communication with local communities and other stakeholders, following the principles of integrity, safety, and environmental responsibility.

API RP 100-1 and 100-2 are recommended practices (RP) of the American Petroleum Institute for the development of shale projects, aimed at ensuring well integrity, environmental protection, and community engagement.

Hydraulic fracturing: Well integrity

This document contains recommended practices for onshore well construction and the design and execution of fracture stimulation with respect to well integrity and fracture containment. The provisions of this document address the following two areas:

a) Well integrity: The design and installation of well equipment in accordance with a standard that:

- Protects and isolates usable-quality groundwater.

- Delivers and executes a hydraulic fracturing treatment.

- Contains and isolates produced fluids.

b) Fracture containment: The design and execution of hydraulic fracturing treatments to contain the resulting fracture within a prescribed geological interval. Fracture containment combines existing parameters, those that can be established during installation, and those that can be controlled during execution:

- Existing: formation parameters with an associated range of uncertainties.

- Established: barriers and well integrity created during well construction.

- Controllable: fracture design and execution parameters.

The guidance in this document covers recommendations for pressure containment barrier design and onshore well construction practices for wells that will undergo hydraulic fracturing stimulation. This document is specifically intended for wells drilled and completed on land, although many of its provisions are applicable to wells in coastal waters.

This document is not a detailed well construction or fracture design manual. It does not apply to continuous injection operations, such as water disposal, water injection, or cuttings reinjection, nor to any other continuous injection operation.

API Standard 100-2 is a complementary document that also contains recommended practices applicable to the planning and operation of hydraulically fractured wells. This document includes recommendations for managing environmental aspects during well planning, construction, and execution.

What advances define modern fracking?

The technological evolution of fracking over the last decade has been extraordinary. The automation of hydraulic fracturing within the context of Industry 4.0 is defined by three fundamental components: surface equipment, downhole sensors, and software control systems.

However, even before these developments, progress was not what it could have been. The expansion and growth of these advances have been important for development, and the regulation of health, safety, and environmental (HSE) standards are a key component of the regulatory framework for oil and gas exploitation.

Electrification transforming operational emissions

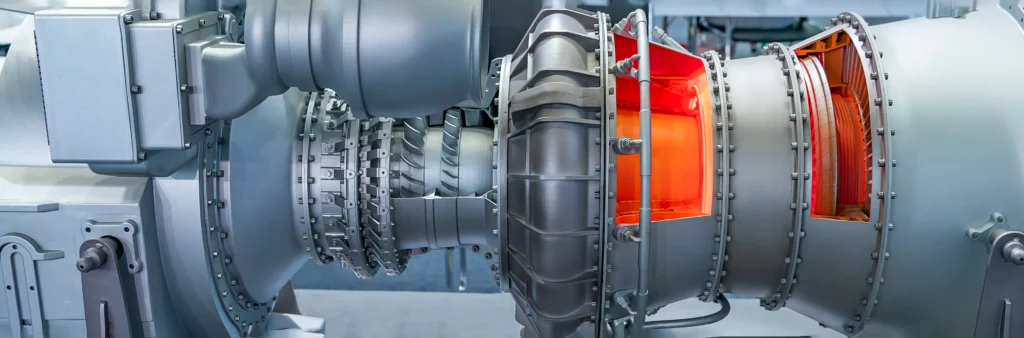

The transition from diesel equipment to electric systems represents perhaps the most visible and transformative change at modern fracturing sites. By providing up to 15,000 horsepower per module, modular power distribution systems can eliminate the need for up to eight traditional units, saving approximately 800 gallons of diesel per hour.

Electric fracturing fleets use natural gas turbines to generate electricity on-site, leveraging the gas produced directly from the reservoir. This circular approach reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 32% to 40% compared to traditional diesel operations.

Natural gas, abundant in shale formations, provides a significantly cleaner energy source than diesel, producing fewer nitrogen oxides, particulates, and greenhouse gases per unit of energy generated.

Gas compressors vs diesel fuel in fracking

Comparative analysis of economic and environmental benefits

| Criterion / Indicator | Gas Compressors | Diesel Systems | Comments / Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating cost per well | Lower, cheaper fuel | Higher, diesel more expensive | Direct savings on fuel and maintenance |

| CO₂ emissions | Significantly lower | High | Environmental improvement and regulatory compliance |

| Noise level | Low | High | Benefits for personnel and nearby communities |

| Maintenance | Less frequent, less costly | More frequent, more costly | Reduced downtime and expenses |

| Fuel availability | Local gas can be used | Diesel requires transport and storage | Simpler logistics with gas |

| Equipment lifespan | Similar or longer | Similar | Depends on brand and model |

Estimated savings per well: Approximately 10–15% reduction in operational costs when using gas compressors compared to diesel systems.

How is the water challenge managed efficiently?

Water consumption in hydraulic fracturing has traditionally been the most controversial aspect of the technology. A modern horizontal well requires between one and five million gallons of water—volumes that can place significant pressure on water resources in arid regions.

Recycling and reuse of flowback and produced water reduce freshwater demand and associated costs for water purchase, transport, and disposal. Modern treatment systems use combinations of balanced flocculation filtration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis to remove suspended solids, bacteria, and chemical contaminants, restoring water to specifications suitable for subsequent fracturing.

Membrane distillation technologies are emerging as particularly promising solutions. Membrane distillation is an emerging technology capable of treating complex and highly contaminated wastewater, allowing drillers to filter and reuse produced water in the oil and gas industry.

Automation that maximizes operational precision

Digitalized fracturing management systems integrate all operational aspects into unified control platforms. In September 2024, Halliburton Company introduced the OCTIV Auto Frac service, the latest addition to the OCTIV intelligent fracturing platform, which digitalizes and automates workflows, information, and equipment across all aspects of fracturing operations.

These platforms connect high-pressure pumps, fluid blenders, proppant injection systems, and downhole sensors into intelligent operational ecosystems.

Automation continuously adjusts injection parameters to maintain target pressures within narrow ranges, prevents overpressure that could damage formations or equipment, and detects anomalies such as incipient plugging long before human operators would perceive them. This constant monitoring reduces nonproductive time by approximately 25% compared to manual operations.

Advanced microseismic monitoring technologies

Accurate characterization of generated fracture networks is essential for optimizing designs and predicting well performance. Microseismic monitoring techniques detect tiny acoustic events generated when rock fractures under hydraulic pressure. Arrays of geophones installed in nearby observation wells or on the surface record these weak seismic signals, enabling triangulation of the exact locations where fractures occur.

The resulting three-dimensional maps reveal the true geometry of fracture networks, often showing significantly greater complexity than theoretical model predictions. Fractures may propagate asymmetrically, activate preexisting natural fracture systems, or behave unexpectedly due to geological heterogeneities.

What is the future of sustainable fracking?

The same horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques that transformed shale production can create underground heat exchange systems, circulating water through deep hot rock to generate clean electricity around the clock. This technology could provide reliable baseload energy that complements intermittent renewable sources such as solar and wind.

Fracking has proven to be an extraordinarily adaptable technology that continues to evolve to address technical, economic, and environmental challenges. Innovations in automation, electrification, water management, and materials are enabling hydraulic fracturing to meet growing global energy demands while progressively reducing its environmental footprint.

The fracking of the future will be radically different from that of a decade ago. Technology is advancing toward cleaner, more efficient, and more closely monitored operations. However, its true sustainability will depend on effective regulation, continuous innovation, and its strategic role within a broader energy transition.

The question is no longer whether fracking can improve, but whether those improvements are sufficient for the climate challenges we face.

Conclusions

Technological innovation has enabled higher production with greater efficiency. The use of advanced horizontal drilling, multi-stage hydraulic fracturing, and real-time monitoring has significantly increased unconventional hydrocarbon recovery while reducing interventions and optimizing resource utilization.

Water management and reuse are the key factors in minimizing environmental impact. The adoption of advanced treatment and recycling technologies, such as membrane distillation, has reduced freshwater demand and wastewater generation, addressing one of the main environmental challenges of hydraulic fracturing.

Digitalization and emissions control strengthen operational sustainability. Automation, advanced analytics, and leak detection systems improve safety, reduce emissions, and support cleaner operations without compromising project profitability.

References

- https://www.api.org/~/media/files/policy/exploration/100-1_e1.pdf

- API RECOMMENDED PRACTICE 100-1

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092041052100454X

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405656125000549

- https://www.halliburton.com/en/about-us/press-release/halliburton-unveils-octiv-auto-frac-service

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can fracking be sustainable?

This is perhaps the most complex and relevant question. The sustainability of fracking depends on how the concept is defined and the time frame under which it is evaluated.

What are the persistent challenges?

Despite technological advances, fracking continues to face fundamental concerns related to water consumption in water-stressed regions, risks of aquifer contamination if rigorous protocols are not implemented, greenhouse gas emissions throughout the entire life cycle, and its incompatibility with long-term net-zero emission goals.

Is there a transition perspective?

Many experts view natural gas extracted through fracking as a “bridge fuel” toward a renewable energy economy, cleaner than coal, yet still dependent on hydrocarbons.