A team of MIT researchers have developed a lightweight polymer film that is nearly impenetrable to gas molecules, raising the possibility that it could be used as a protective coating to prevent corrosion of solar cells and other infrastructure, and to slow the aging of packaged foods and medicines.

The development of a new lightweight polymer film

The polymer, which can be applied as a film as thin as nanometers, completely repels nitrogen and other gases, as detected by laboratory equipment, the researchers found. This degree of impermeability never before seen in any polymer rivals the impermeability of crystalline materials of reduced molecular thickness, such as graphene.

Our polymer is quite unusual. Obviously, it is produced from a solution-phase polymerization reaction, but the product behaves like graphene, which is impermeable to gases thanks to its perfect crystal. However, when examining this material, you would never mistake it for a perfect crystal, says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT.

The polymer film, which the researchers describe today in Nature , is manufactured by a process that can be scaled up to large quantities and applied to surfaces much more easily than graphene.

Strano and Scott Bunch, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Boston University, are the lead authors of the new study. The paper’s lead authors are Cody Ritt, a former MIT postdoctoral researcher and current assistant professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder; Michelle Quien, a graduate student at MIT; and Zitang Wei, a research scientist at MIT.

The Strano lab first reported on the novel material-a two-dimensional polymer called 2D polyaramide that self-assembles into molecular sheets via hydrogen bonds-in 2022. To create these 2D polymer sheets, something never before achieved, the researchers used a building block called melamine, which contains a ring of carbon and nitrogen atoms. Under the right conditions, these monomers can expand in two dimensions, forming nanometer-sized disks. These disks are stacked one on top of the other, linked by hydrogen bonds between the layers, giving the structure great stability and strength.

That polymer, which the researchers call 2DPA-1, is stronger than steel but has only one-sixth the density of steel.

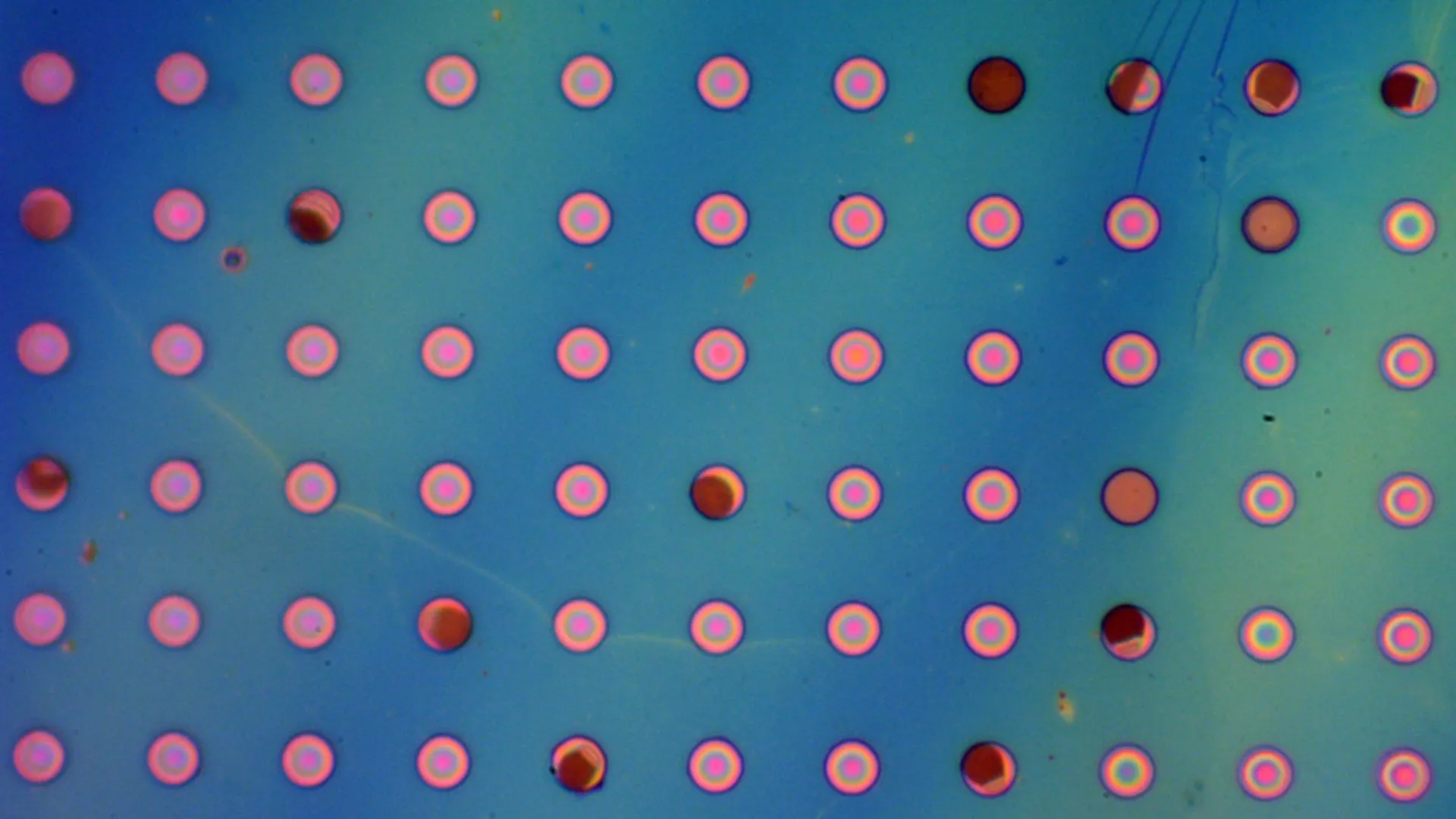

In their 2022 study, the researchers focused on testing the material’s strength, but also conducted preliminary studies on its permeability to gases. For these studies, they created “bubbles” from the films and filled them with gas. With most polymers, such as plastics, the gas trapped inside leaks through the material, causing the bubble to deflate rapidly.

However, the researchers found that the 2DPA-1 bubbles did not collapse; in fact, the bubbles they created in 2021 are still inflated. “At first I was quite surprised,” says Ritt. “The behavior of the bubbles did not follow that expected for a typical permeable polymer. This forced us to rethink how to properly study and understand molecular transport through this new material.”

“We performed a series of painstaking experiments to first demonstrate that the material is molecularly impermeable to nitrogen,” Strano says. “It could be considered tedious work. We had to create microbubbles of the polymer and fill them with a pure gas such as nitrogen, and then wait. We had to repeatedly check over an extremely long period of time that they didn’t collapse in order to report the record value for impermeability.”

Traditional polymers allow the passage of gases because they consist of a tangle of spaghetti-like molecules, loosely bonded together. This leaves small spaces between the strands. Gas molecules can leak through these spaces, which is why polymers always exhibit some degree of gas permeability.

However, the new 2D polymer is essentially impermeable due to the way the layers of disks are bonded together.

The fact that they can be compacted flat means there is no volume between the two-dimensional disks, which is unusual. With other polymers, there is still space between the one-dimensional chains, so most polymer films allow at least a small amount of gas to pass through, Strano says.

George Schatz, professor of chemistry and chemical and biological engineering at Northwestern University, described the results as “remarkable.”

“Normally, polymers are reasonably permeable to gases, but the polyaramides reported in this paper are orders of magnitude less permeable to most gases under industrially relevant conditions,” says Schatz, who was not involved in the study.

In addition to nitrogen, the researchers also exposed the polymer to helium, argon, oxygen, methane and sulfur hexafluoride. They found that the permeability of 2DPA-1 to these gases was at least 1/10,000 greater than that of any other existing polymer. This makes it almost as impermeable as graphene, which is completely impervious to gases thanks to its flawless crystalline structure.

Scientists have been working on developing graphene coatings as an anti-corrosion barrier in solar cells and other devices. However, scaling up the creation of graphene films is difficult, largely because they cannot be painted onto surfaces.

“We can only produce crystalline graphene in very small portions,” Strano says. “A small portion of graphene is molecularly impermeable, but it doesn’t scale. Attempts have been made to apply it with paint, but graphene does not adhere to itself, but slides when cut. Graphene sheets moving against each other are considered to be virtually frictionless.”

On the other hand, the 2DPA-1 polymer adheres easily due to strong hydrogen bonds between the layered disks. In this paper, the researchers demonstrated that a layer as thin as 60 nanometers could extend the lifetime of a perovskite crystal for weeks. Perovskites are promising materials as inexpensive and lightweight solar cells, but they tend to degrade much faster than the silicon solar panels that are widely used today.

A 60-nanometer coating extended the perovskite’s lifetime to about three weeks, but a thicker coating would offer longer protection, according to the researchers. The films could also be applied to a variety of other structures.

With a waterproof coating like this, you can protect infrastructure such as bridges, buildings, railways, basically anything exposed to the elements. Automotive vehicles, aircraft and boats could also benefit. Anything that needs corrosion protection. The shelf life of food and medicines can also be extended with these materials, says Strano.

The other application demonstrated in this article is a nanoscale resonator, basically a small drum that vibrates at a specific frequency. Larger resonators, with sizes of about 1 millimeter or less, are found in cell phones, where they allow the phone to pick up the frequency bands it uses to transmit and receive signals.

“In this paper, we created the first 2D polymer resonator, something that can be done with our material because of its impermeability and strength, like graphene,” Strano says. “Currently, the resonators in phones and other communication devices are large, but work is underway to reduce them through nanotechnology. Reducing them to less than a micron would be revolutionary. Cell phones and other devices could be smaller and reduce the power consumption needed for signal processing.”

Resonators can also be used as sensors to detect very small molecules, including gas molecules.

The research was funded, in part, by the Center for Enhanced Nanofluidic Transport-Phase 2, an Energy Frontiers Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, as well as the National Science Foundation.

Source and photo: MIT