Mooring incidents are common and serious. OCIMF’s Mooring Equipment Guidelines (MEG4) notes that, in 2007-2016, the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch recorded 37 reports of mooring line failures. In the five years to 2021, the International Group of P&I Clubs recorded 858 injuries and 31 fatalities during mooring operations. Australia’s regulator (AMSA) received 227 mooring-related reports in 2010–2014; 22% caused injury, and 62% involved design/equipment factors.

Human factors show up in nearly every event. Errors happen in interaction with conditions and systems. Addressing those interactions reduces incidents and improves reliability.

Typical misconceptions include the following:

- “Training fixes it.” Training matters, but it is a lower-order control and cannot compensate for poor layout, hard-to-use controls, or unseen loads.

- “Fatigue is the root cause.” Fatigue contributes, but most mistakes arise from design, equipment, or task demands that make error likely.

- “Write another procedure.” Procedures help, yet the priority is to eliminate or engineer out hazards; administrative controls come later.

People will make mistakes. Mooring systems must be designed as if error is normal, not rare.

Human factors principles

OCIMF’s human factors principles are straightforward: people will make mistakes; their actions usually make sense to them at the time; mistakes arise from conditions and systems; the people doing the work know the most about it; design can reduce mistakes; and leaders shape the conditions and how we learn from failure.

MEG4 converts those ideas into design practice. It asks designers to analyze safety-critical tasks and apply human-centered design (HCD), not just add procedures later. This involves using task analysis and human reliability analysis to identify error traps and performance-shaping factors before steel is cut.

The hierarchy of controls

Prevention beats protection. The hierarchy of controls sets the order in which barriers should be prioritized: eliminate (physically remove the hazard), substitute (replace the hazard), engineer (isolate people from the hazard), organize (change the way people work), and then protect the worker with personal protective equipment (PPE). Controls at the top of the hierarchy should be prioritized.

This is a paradigm shift. According to AMSA’s data, in the past, after mooring injuries, only 3% of remedial actions eliminated the hazard, and 10% utilized engineering controls. 87% were administrative/PPE fixes, the least effective.

Examples of the implementation of safety guidance for mooring systems

Elimination

- Consider alternative mooring methods that remove mooring lines (and their snap-back risk) altogether. Even where full elimination is not feasible, remove tasks that require personnel to enter high-risk zones.

Substitution

- Use reduced-recoil mooring lines. Replace conventional HMSF lines with reduced recoil risk constructions that are designed to fail incrementally and dissipate energy. This lowers the energy released if a line parts and increases warning time.

- Prefer split-drum winches over undivided drums. Split drums retain only one layer on the tension part, maintain more consistent brake performance, and prevent line embedding damage, thereby reducing error-prone interventions.

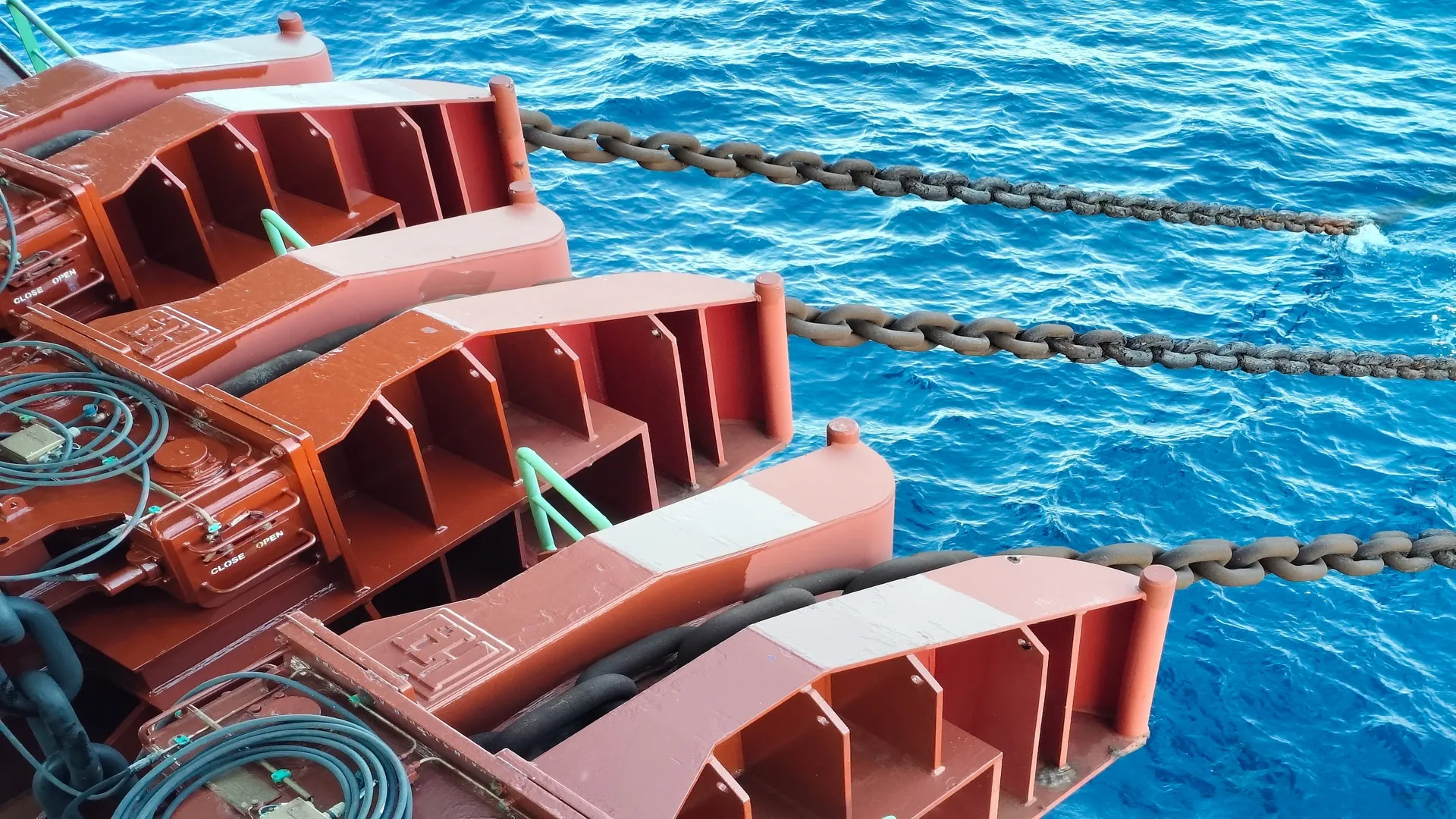

- Upgrade fairleads for the job. In high tidal range or STS operations, substitute open roller fairleads with closed/closed-roller/universal fairleads to prevent line jump-out. Ensure geometry suits expected line angles.

- Be cautious with elastic tails. Traditional steel/ HMSF lines with synthetic tails add elongation, increase stored energy, and enhance snap-back severity. Where the design allows, substitute toward configurations that achieve energy management through brake rendering and geometry instead of added tail elasticity.

- Avoid jacketed lines unless necessary. Jackets protect fibres but hinder inspection and field splicing; if you must use them, substitute them in a documented inspection and testing regime to preserve service-life confidence.

Isolation and engineering

- Design out snap-back exposure. Do not rely on painted snap-back zones; MEG4 warns they create a false sense of safety. Treat the entire mooring deck as an elevated-risk area and control access with barriers and signs.

- Achieve direct leads from winch to fairlead; minimize lines crossing open deck; avoid sharp leads and pedestal rollers. These steps reduce bend-induced strength loss and unpredictable recoil paths.

- Remote operation and monitoring. Place controls away from hazard zones; add CCTV and protected or elevated oversight positions. Integrate mooring line load monitoring to enable crews to set and maintain safe tensions during berthing and while alongside.

- Design for visibility. Operators must clearly see the winch, gauges, personnel, ship’s side, and signalers, by day and night, without torches.

- Right-sized manpower and communications. Complex, multi-winch operations require sufficient personnel and robust communication; design assumptions about crew numbers must be captured and validated.

Organizational measures

Use permits, procedures, training, and time limits, and separate mooring areas from general walkways. These matters, but they do not replace elimination and engineering.

What designers should consider

- Start with human-centered design. Plan for “work as done,” not “work as imagined.” Involve execution teams early to reveal error traps and practical constraints.

- Prioritize elimination and engineering. Remove the need for people to be in snap-back paths. If not possible, isolate them using remote operation, barriers, and protected positions.

- Design for visibility, awareness, and knowledge of load. Unobstructed views, reliable communications, good lighting, and real-time load monitoring reduce guesswork and rush.

- Shape the layout to reduce error. Favor direct leads; minimize deck crossings; avoid sharp bends and excessive roller use; protect fairleads; specify adequate bend radio.

- Specify the people and the plan. Define the expected number of operators and roles. Document assumptions in the design file and ensure the mooring systems management plan can be executed with available manpower.

- Beware safety theatre. Do not paint fixed snap-back zones; manage the entire deck as an elevated-risk area with controlled access.

- Design for learning and resilience. Build feedback loops to ensure that experience from inspections, incidents, and safety-critical task reviews improves design and practice across the fleet.

Conclusion

Mooring is a high-risk activity. The record of incidents and accidents over the last decade shows that relying solely on perfect human performance is not a viable plan. Design must assume mistakes will happen and make those mistakes difficult to trigger, easy to detect, and easy to recover from.

Designers and managers should follow the hierarchy of controls: eliminate hazards where possible; substitute and isolate when not; apply strong engineering; and only then lean on procedures, training, and PPE.

Humans will make mistakes. Sound mooring systems are designed to prevent those mistakes from causing incidents.

This article was developed by the specialist Filipe Santana and published as part of the sixth edition of Inspenet Brief September 2025, dedicated to technical content in the energy and industrial sector.